- Details

- By Kaili Berg

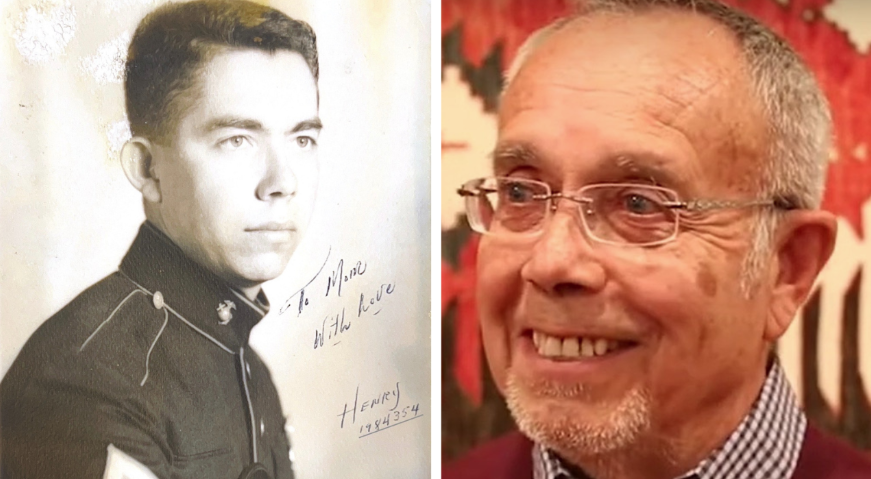

For 81-year-old Marine Corps veteran Joseph Henry Suina, healing didn’t end when he came home from Vietnam. In many ways, his healing has been a long journey.

Suina, a tribal councilman and former governor of Cochiti Pueblo in New Mexico, enlisted in the Marine Corps in 1962 — the quickest path, he said, “to see the world beyond the Pueblo.”

Barely out of high school, he joined the Fifth Marine Division and shipped out with what was known as the “floating battalion.” By 1964, he was in Vietnam, witnessing a level of violence and chaos far removed from his quiet community.

“I was used to hunting,” Suina told Native News Online. “I was not used to being hunted.”

As the only Native Marine in his unit, he faced stereotypes that often put him in greater danger.

“People assumed I could smell or see the enemy better because I was Native,” he said. “So I was put out front more than I should have been.”

Suina served two tours, returning home with shrapnel wounds, PTSD, and memories he couldn’t speak about.

When he arrived back in Cochiti Pueblo, he knew immediately something was wrong. The stress, nightmares, and sudden triggers followed him everywhere.

“You think you’re coming home to peace,” he said. “But I was looking over my shoulder all the time.”

He also returned to a country unprepared — and in some cases unwilling — to welcome Vietnam veterans. He remembers being shouted down by anti-war protesters while speaking in a college classroom soon after he came home.

“It added another layer of guilt,” Suina said. “People forget what that time was like.”

For decades, Suina sought help through the VA, but the care, he said, “was not very good.” Early on, what helped him most were the traditional healers in his own community.

The turning point came when he entered the Home Base Intensive Clinical Program (ICP) in Boston, supported by the Bob Woodruff Foundation. Although he was the only Native veteran in his cohort at the time, it was the first time he received deep, trauma-focused care.

“Their care was intense. They examined every part of what you’re going through,” he said. “That level of attention — we don’t get that out here in regular veterans programs.”

His family joined sessions on Zoom, something he describes as essential.

“PTSD doesn’t just affect the veteran,” Suina said. “It affects the whole family. They need strategies too.”

That family-centered model is a core part of Home Base’s approach. Abby Vankudre, program officer at the Bob Woodruff Foundation, said their investment in the Native American ICP is about ensuring Native veterans finally receive the kind of care they deserve.

“Our partnership with Home Base is an important investment in ensuring that evidence-based treatments are accessible,” Vankudre said. “This life-changing program helps our nation’s veterans, together with their families, move from surviving to thriving. The Home Base team recognizes the complex history of the Native American and Indigenous veteran population and have structured the program to build trust.”

Home Base staff undergo Native cultural competency training, work closely with Native advisors, and incorporate cultural elements such as medicine bundles, Talking Circles, and blessings into the program.

Since Suina completed his program, Home Base has expanded its Mobile Native ICP, bringing clinicians directly into tribal communities so veterans don’t have to travel long distances to receive culturally aligned care.

Marcus Denetdale (Diné), an Air Force veteran and Regional Associate Director for Southwest & Tribal Relations at Home Base, said the goal is to honor Native veterans in ways conventional programs have never fully done.

“Home Base’s Mobile Native ICP is about more than expanding access to mental health care,” Denetdale said. “It’s about meeting Native veterans where they are and delivering care that honors their lived experience. We can bring this culturally grounded, life-changing program directly to Native communities and ensure veterans and their families can access care close to home.”

Today, Suina often speaks to fellow veterans — Native and non-Native — about the importance of seeking help.

“There is no shame in it,” he said. “You need to learn to recognize the signs and stop them before they hurt you or your family.”

He also sees a larger movement taking shape across Indian Country, where trauma is finally being named, understood, and addressed.

“One thing Vietnam gave me is a deep appreciation for life,” Suina said. “It is so fragile. We need to be healthy and strong, and know that we are a proud people, a good people. We’re here, and we’re going to continue to be here for a long time to come.

More Stories Like This

Wilton Rancheria Donates $50,000 and 418 Turkeys to Food Bank Amid Shutdown AftermathAlaska’s commercial salmon harvest rebounds after ultra-low harvest last year

Ak-Chin Selected for New IHS Tribal Health Center

The Indian Health Service Is Flagging Vaccine-Related Speech. Doctors Say They’re Being Censored.