- Details

- By Chez Oxendine

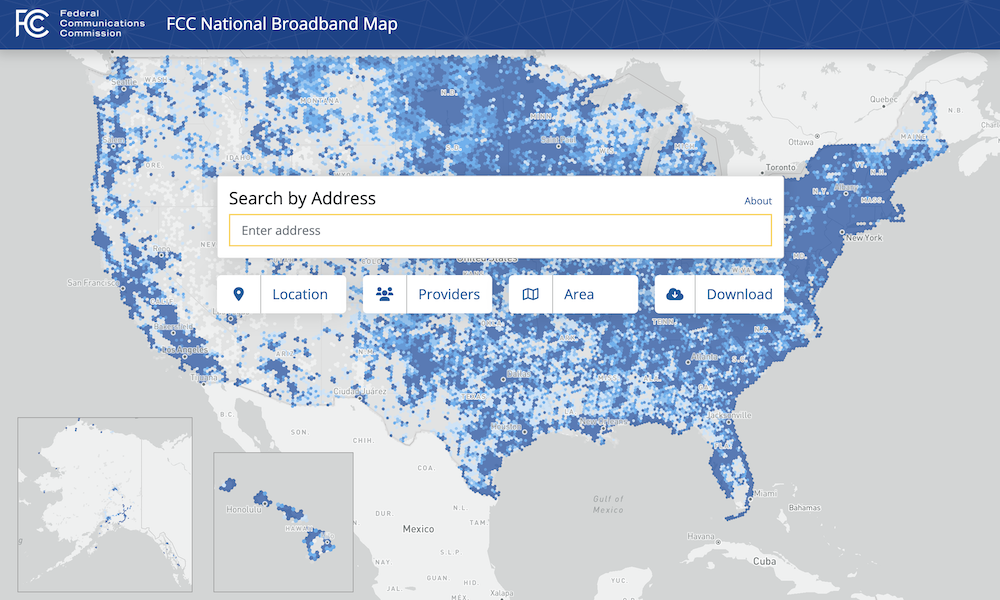

The Federal Communications Commission has launched the interactive map to encourage individuals and families to self-report on their broadband connectivity. The site also includes a bulk challenges page where Tribal governments can comment on broadband connectivity on Tribal lands.

The data will be utilized to allocate funding for the National Telecommunications and Information Administration’s Broadband Equity, Access, and Development (BEAD) program.

More than half of Indian Country remains offline or underserved, thanks to poor connectivity in rural areas and a fiber backbone that avoids many tribal reservations, per prior Tribal Business News reporting. Part of the problem lies in incorrect data: the FCC census has routinely overstated the level of service in many rural communities — in particular tribal communities, according to Matthew Gregg, a senior economist at Minneapolis-based Center for Indian Country Development.

“The main reason is that internet service providers could claim that a location is completely served if the ISP provided internet to at least one household within a given location or if the ISP could serve that location soon,” Gregg told Tribal Business News. “The new FCC broadband map is meant to address these inaccuracies.”

Tribal or other officials who want to make bulk challenges and individual households are encouraged to visit the new National Broadband Map website and report connectivity issues or a lack of service by Jan. 13, according to an FCC statement.

The FCC’s updated census comes after years of reflection and questions about tribal connectivity. COVID-19 has thrown the issue of Indian Country’s connectivity into sharp relief as communities suddenly in need of telehealth and distance learning services could not consistently connect to video calls or access online classes.

Federal responses to the increased need have included spectrum auctions, technical assistance, and an unprecedented flood of funding for infrastructure and adoption programs. As a result, good data becomes a crucial component in determining grants and support for a given initiative, Gregg said.

The BEAD program, for example, aims to direct $42.5 billion in total at the broadband problem, distributed to — and eventually through — state governments. Since tribes can access that funding through partnerships with their surrounding states, good data can funnel more of that pot to those most in need of it, Gregg said.

“More accurate data will lead to a more efficient allocation of BEAD dollars,” Gregg said. “States with more unserved locations will receive more BEAD funding.”

In addition to this year’s allocation of BEAD funding, the Tribal Broadband Connectivity Program is nearing the end of its initial $1.98 billion pot of funding — though that amount falls well short of the initial $5 billion requested during the program’s first application period.

The National Telecommunications and Information Administration has promised a second funding opportunity of another $1 billion will arrive “soon,” according to recent statements, but has not specified when applications for that opportunity will begin.

Good data will play a role in where that money goes, according to prior Tribal Business News reports, as industry experts and tribal leaders continue discussing their needs with federal supporters.

Make A Monthly Donation Here

Make A Monthly Donation Here

A January 2022 story in Tribal Business News points to a Senate hearing on the issue, during which Sen. Brian Schatz (D-Hawaii) said the FCC’s most recent data was “worse than nothing” since it pointed support efforts in the wrong direction.

“If we had nothing, we could use our intuition. Instead, we have actual bad data, which leads policymakers at the legislative level to engage in magical thinking about who has broadband connectivity and who doesn’t,” Schatz said. “It has to do with how the corporations want to count connectivity. It’s having an army of really well-educated individuals who work as hard as they can to remove their common sense when they’re trying to analyze whether people have connectivity to the internet.”

Lack of connectivity has been an ongoing problem throughout Indian Country as a result of issues such as digital redlining. Even when Natives can get online, they often pay more for the privilege and for less speed than their urban counterparts.

“Research conducted by the Center for Indian Country Development reveals that households in Indian Country pay substantially more for basic home internet service than households located in neighboring, non-tribal areas,” Gregg said. “Secondly, additional research…shows that business owners are reluctant to operate their establishments in Indian Country due to the lack of reliable internet.”

Connectivity also plays a central role in the exodus of young people from Native reservations, exacerbated by the inability to join the advent of remote work.

“From a social perspective, more reliable, faster internet allows for greater access to the remote work revolution, which could curb the outmigration of young, educated individuals from tribal communities,” Gregg said. “Greater deployment will lower prices and spur local economic development.”

More Stories Like This

Native News Weekly (August 25, 2024): D.C. BriefsUS Presidents in Their Own Words Concerning American Indians

Native News Weekly (January 18, 2026): D.C. Briefs

Federal Judge Orders ICE to Halt Use of Pepper Spray, Arrests of Peaceful Protesters in Twin Cities

Tunica-Biloxi Cultural Leader John D. Barbry Walks On

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher