- Details

- By Jenna Kunze

COWESSESS, Saskatchewan — Donning a Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls pin on Thursday, Chief Cadmus Delorme of the Cowessess First Nation in Saskatchewan announced the discovery of as many as 751 unmarked graves on what was formerly the Marieval Indian Residential School.

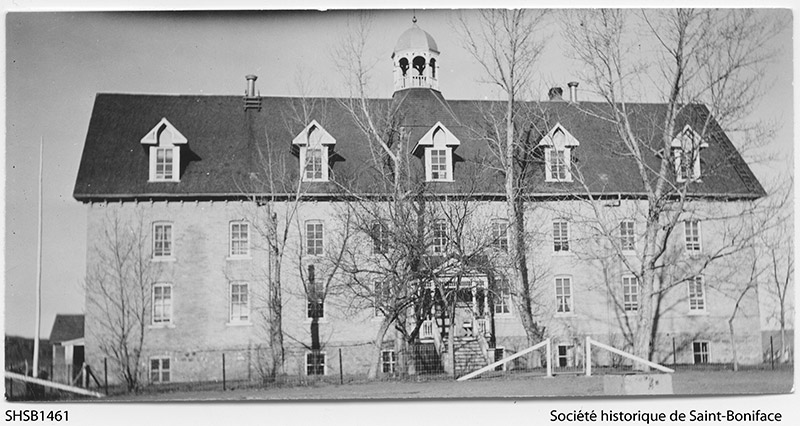

The Marieval Indian Residential School operated from 1899 to 1996, overseen by the Roman Catholic Church. It was among the roughly 150 residential schools in Canada—the majority of which were in Saskatchewan—serving the express purpose of assimilating Indigenous youth by stripping them of their culture.

Want more Native News? Get the free daily newsletter today.

“Over the past years, the oral stories of our elders, of our survivors, and friends of our survivors have told the stories that knew these burials were here,” Delorme said in a virtual press conference Thursday. Indigenous youth came to Marieval from Treaty 4 and Treaty 2 territories, including the White Bear First Nation, the Ochapowace Nation, the Zagime Anishinabek, and the Kahkewistahaw First Nation.

He stressed that the site is not a mass grave, but an identified graveyard until the Catholic Church possibly removed headstones in 1960.

“In 1960, there may have been marks on these graves,” he said. “The Catholic Church representatives removed these headstones, and today they are unmarked graves.”

Cowessess First Nation began surveying what is now its community gravesite with ground penetrating radar on June 2, following the news from the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation in British Columbia, where an unmarked mass grave holding the remains of 215 Native children was discovered.

A screenshot of Chief Cadmus Delorme of the Cowessess First Nation. (Photo/Facebook)

A screenshot of Chief Cadmus Delorme of the Cowessess First Nation. (Photo/Facebook)

Delorme said the radar detected 751 “hits” of unmarked graves, though the machine has a 10 to 15 percent error rate, which confirms at least 600 gravesites with certainty. He also said the First Nation can’t yet confirm if there is more than one person buried under each detected “hit,” though they will verify an exact number of burial sites in the coming weeks.

According to oral histories, he added, some of those graves might belong to adults.

“Some may have went to the church and from our local towns, and they could have been buried here, as well,” Delorme said.

The initial search is Phase 1 of a multi-phase, yearslong process, the Chief said. Phase 1 will also include a sweep of other locations on the Cowessess First Nation believed to contain remains of unbaptized children, or young mothers not yet of age for baptism.

‘A crime against humanity’

Also on the call Thursday was Bobby Cameron, Chief of the Federation of Sovereign Indigenous Nations, which represents the 74 First Nations in Saskatchewan.

“This was a crime against humanity,” Cameron said. “The only crime we ever committed as children was being born Indigenous.”

Elder Florence Sparvier of Cowessess First Nation, also on the video call, is a Marieval Indian Residential School survivor. At the time, she said if a Native parent were to deny the federal government's request to send their kid to residential school, one parent would be subject to arrest.

Sparvier, a third-generation attendee in her family of the Marieval school, said the nuns at the school were condemning of Indigenous people. “They told us our people, our parents, our grandparents… they didn't have a way to be spiritual, because we were all heathens,” she said. “So we learned how to not like who we were.”

A screenshot of elder Florence Sparvier, 80, of the Cowessess First Nation (left). Sparvier is a survivor of the Marieval Indian Residential School. (Photo/Facebook)

A screenshot of elder Florence Sparvier, 80, of the Cowessess First Nation (left). Sparvier is a survivor of the Marieval Indian Residential School. (Photo/Facebook)

Cameron swore local Indigenous leadership would not stop until it finds all of its missing children, including a search of Indian Residential Schools, sanatoriums within local hospitals, and “all of the sites where people were taken and abused, tortured, neglected and murdered.”

“We had concentration camps here in Canada, in Saskatchewan,” Cameron said. “They were called Indian Residential Schools.”

‘We all must put down our ignorance’

According to Delorme, Canadian Ministers Miller and Bennett reached out to Cowessess today to offer support.

Moving forward, the Cowessess First Nation will also be investigating the events surrounding the 1960 headstone removal from the cemetery, the chief said. “Removing headstones is a crime in this country, and we are treating it like a crime at the moment.”

According to a local law passed in 2001 in Saskatchewan, The Cemeteries Act of 1999, it is illegal to disturb a gravesite, including the removal of a headstone. It is unknown whether this law might retroactively apply to the 1960s.

Archbishop Don Bolen of the nearby Archdiocese of Regina, which oversaw the Marieval Indian Residential School at the time, wrote in an apology letter to the Cowessess First Nation that “one priest who served in the region in the 1960’s destroyed headstones in a way which was reprehensible.”

Moreover, Delorme said the First Nation will work to identify and honor those buried in the unmarked graves with the help of documents not yet released by the Archdiocese of Regina.

He also added that the Indigenous peoples in Canada need an apology from Pope Francis for the resounding impact of residential schools on survivors and their descendants. On June 5, the Pope expressed “sorrow” about the shocking discovery in Kamloops, but offered no apology or accountability on behalf of the Catholic Church.

“An apology is one stage of many in the healing journey,” Delorme said.

Assembly of First Nations National Chief Perry Bellegarde echoed Delorme’s call for an apology in a statement released Thursday. “We must never forget our children were targeted and placed in a racist system purposely designed to stamp out every aspect of who we are – our languages, our cultures, our teachings,” he wrote. “I support Chief Delorme in his call for healing and for an apology from His Holiness, Pope Francis.”

“Everybody has to accept maybe the ignorance, or the accidental racism that the education system has told before, it is already being changed,” Delorme added. “And investment in healing from the core outwards has to happen. Once truth is given, and told, and accepted, then reconciliation will prevail.”

The Archdiocese of Regina did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

Andrew Kennard contributed reporting.

More Stories Like This

Native News Weekly (August 25, 2024): D.C. BriefsDeb Haaland Rolls Out Affordability Agenda in Albuquerque

Boys & Girls Clubs and BIE MOU Signing at National Days of Advocacy

National Congress of American Indians Mourns the Passing of Former Executive Director JoAnn K. Chase

Navajo Nation Mourns the Passing of Former Vice President Rex Lee Jim

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher