Sophie High Dog was the age of a kindergartener when she was taken by a missionary from the Rosebud reservation in South Dakota and placed in a notorious boarding school in Pennsylvania: Five years old.

That was more than a century ago, and still Sophie hasn’t come home. The little girl was sent away from Carlisle Indian Industrial School in 1895 by Captain Richard Henry Pratt— the school’s superintendent and the speaker behind the “Kill the Indian, Save the Man” slogan—when she began showing signs of illness “that presaged an early death,” according to a 1900 newspaper article.

She was brought to a home that was run by the Episcopal Church in Saratoga Springs, New York, where her health improved and she lived for another several years before she died of an unknown sickness. Letters she wrote to the missionary who took her, Miss Meade, were regularly published in the local newspaper. Meade belonged to the Albany Indian Association, a women's group founded in 1883 “for the education of Native children,” and the group used Sophie as a marketing tool to solicit donations and gifts at Christmas time.

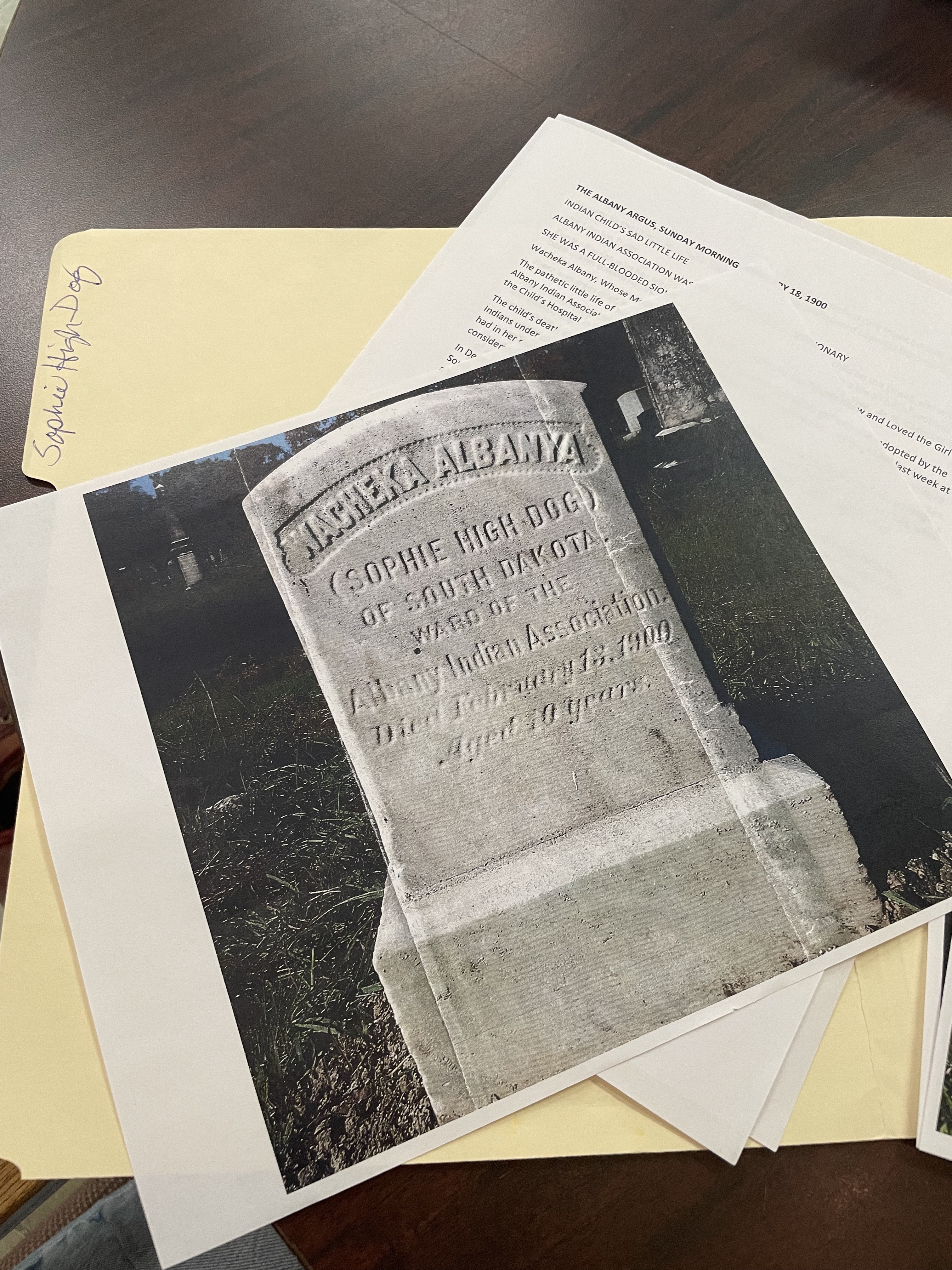

Records show that Sophie had two names—the other name, “Wacheka Albanya,” might have been given to her in Albany because it sounded “Indian,” according to Paula Lemire, the historian at the Albany Rural Cemetery, where she’s buried.

When Sophie died at ten years old on Feb. 13, 1900—her records indicate she had tuberculosis—the Albany Indian Association buried her at the Albany Rural Cemetery.

‘What would she have thought?’

The known newspaper articles published about Sophie illustrate the racist and paternalistic attitude white society adopted towards Native Americans during the boarding school era.

In the Albany Argus’s 1900 story announcing Sophie’s death, the headline reads “Indian Child’s Sad Little Life.” It goes on to allege that Sophie’s mother “threw her away” and paints the Indian Association as the heroes who “took her from a pagan home of wickedness… and put into the few short years of her life the loving faith and simple joys that belong to happy childhood.”

According to Lemire, other records say that Sophie was an orphan and was in the custody of her uncle at the time she was taken by Miss Meade.

“It's so condescending to the indigenous people, how they write about us,” Ione Quigley, Rosebud tribal historic preservation officer, told Native News Online in May. She was contacted by the cemetery’s historian in January to begin the process of disinterring Sophie and returning her home, and she’s been held up trying to locate Sophie’s descendants for their approval and to figure out who will pay for her return.

But first, Quigley wants to set the record straight:

“First of all, [the U.S. government] put us in a situation where it's hard to provide for our families anymore. And then you take away the lifestyle that we had to subsist and to live,” she said. “The fact that they have looked upon us as people that throw away our kids, that’s not true. We can’t believe that part, that’s just their assumption.”

Though Sophie was given a proper headstone that indicates that she was cared for, Qugley said that doesn’t make up for the painful writings about her and about the Rosebud community.

“Should she have survived, what would she have thought? That she was unwanted. That she got thrown away. Thrown away. That’s a really strong way to put it. What would that have done to her?”

Sophie High Dog Gravestone, from Ione Quigley's record folder on Sophie at the Tribal Historic Preservation Office at Rosebud Sioux. (Photo/Jenna Kunze)

Sophie High Dog Gravestone, from Ione Quigley's record folder on Sophie at the Tribal Historic Preservation Office at Rosebud Sioux. (Photo/Jenna Kunze)

Who will pay?

The U.S. Army told the Rosebud Tribe that it would not bear any of the costs of returning Sophie home, since she was not buried in the Carlisle cemetery.

“The Army’s authority to disinter and fund the return of children who attended the Carlisle Indian Industrial School is limited to those children who are buried in the Carlisle Barracks Post Cemetery, due to the Army assuming responsibility for the cemetery after the school had closed,” Office of Army Cemeteries director Renea Yates said in a statement to Native News Online. “The Carlisle Indian Industrial School was under the control of and operated by the Bureau of Indian Affairs at that time Sophie High Dog was sent to Albany, and was never under the control of the Department of the Army.”

A contact at the Episcopal Church told Quigley the church didn’t have any money to return buried children.

“It kind of angers me towards the Episcopal church, because they have known throughout all these years that she was buried there,” she said. Though the cemetery is nondenominational, its early board members were mostly Episcopalian. “And I'm like, well, you had the money to take her. You had the money to bury her and buy her a headstone. You're telling me you just don't have the money to bring her home.”

Lemire told Native News Online that she’s been aware of Sophie’s story for roughly 20 years, but that she thought management at Albany Rural Cemetery would be reluctant if she suggested that Sophie be repatriated.

“Let's just say, they were here to basically bury people, operate the crematorium, and keep the gates open,” she said. “They didn’t really focus on anything beyond that. That’s why I waited several years before I brought up the issue; I had to wait until they would be more open to the idea.”

Adult disinterment at the Albany Rural Cemetery costs $950, though Lemire said it may be less for a child.

She added that she hopes fundraising efforts and local volunteer services, such as the local funeral home who said they could help with shipping Sophie’s remains home, will cover the full cost of repatriation.

“We have had people who've said, ‘if there's any fundraising to help cover this, we're willing to donate,’ because I've mentioned Sophie and a couple of presentations I've given on the cemetery, and there's people who are willing to step up and assist,” she said.

Quigley is tentatively planning a summer trip to Albany to bring Sophie home.

This will be her second repatriation trip in as many years; Last summer she traveled with Rosebud Sicangu Youth to bring home nine of their ancestors buried at Carlisle.

“It’s a commitment, and I’ve seen and felt how sacred it is,” Quigley, who is a survivor of Saint Francis Mission, an Indian Boarding School on the Rosebud reservation. “It humbles me to think that I was able to help them come home and come to a place of peace, and then to move on.”

More Stories Like This

50 Years of Self-Determination: How a Landmark Act Empowered Tribal Sovereignty and Transformed Federal-Tribal RelationsThe Shinnecock Nation Fights State of New York Over Signs and Sovereignty

Navajo Nation Council Members Attend 2025 Diné Action Plan Winter Gathering

Ute Tribe Files Federal Lawsuit Challenging Colorado Parks legislation

NCAI Resolution Condemns “Alligator Alcatraz”

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher