- Details

- By Kaili Berg

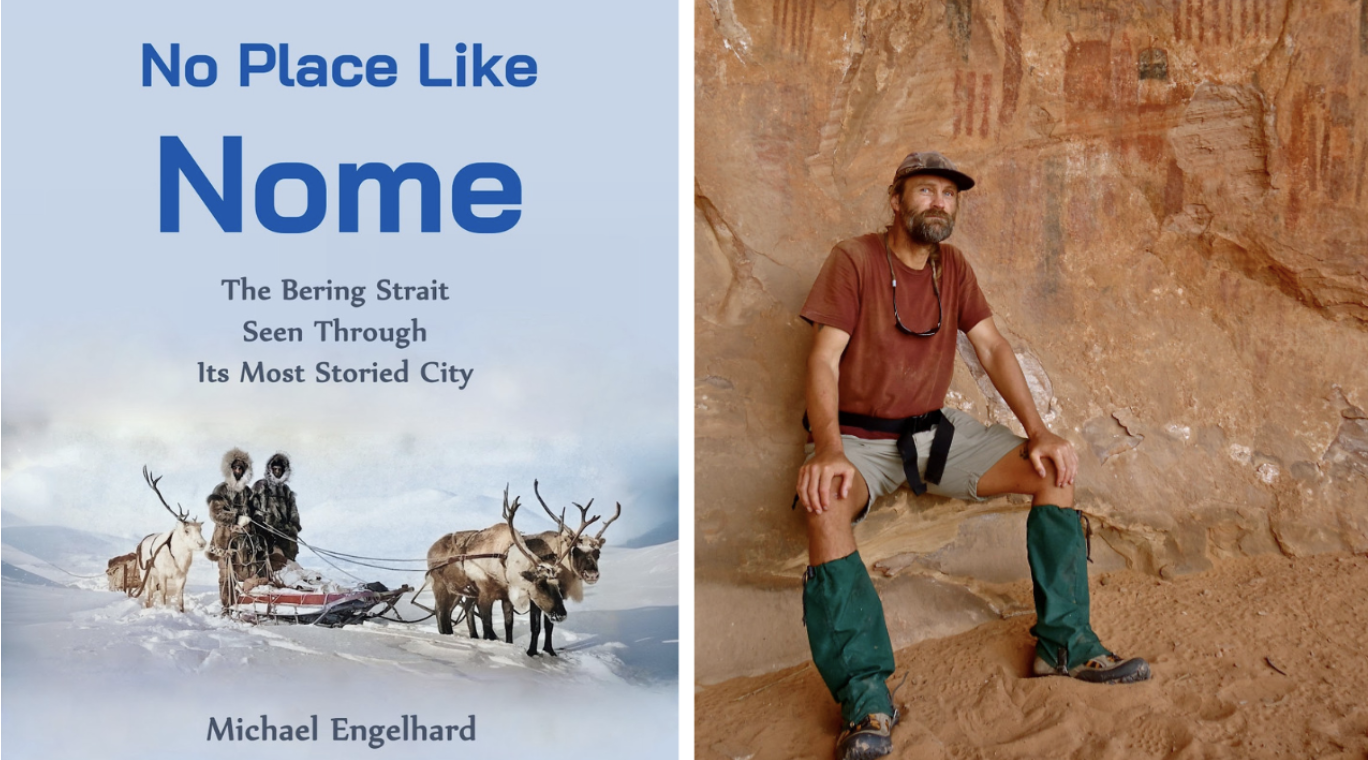

Author and cultural anthropologist Michael Engelhard is shining a new light on one of Alaska’s most storied towns in his forthcoming book, No Place Like Nome.

Blending lived experience, historical research, and oral traditions, Engelhard paints a portrait of a community often misunderstood or reduced to stereotypes, while centering the Indigenous voices that continue to define the region.

Engelhard lived in Nome for three years, but his connection to northwestern Alaska stretches back further. As a graduate student, he participated in a subsistence and land use study, spending time in remote communities and speaking with elders.

He later worked as a wilderness guide, traversing the Brooks Range by foot and raft. These experiences gave him not only a respect for the land but also an outsider’s perspective that allowed him to see how deeply history, culture, and environment are interwoven in the Bering Strait region.

Bill Fitzhugh of the Smithsonian's Arctic Studies Center in Anchorage praised the book for "capturing a town and its peoples and cultures with accuracy and humor, and for centering its indigenous residents in that story."

Engelhard told Native News Online the inspiration behind the book, the challenges of representing Nome’s layered identities, and the importance of centering Indigenous perspectives.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What inspired you to write No Place Like Nome, and what do you hope readers take away from it?

I lived for three years in Nome, and as the subtitle says, it is the most storied city I’ve ever lived in. Positioned at a crossroads of continents and cultures, North America and Asia, Anglo and Inupiaq, it is rich in characters and history dating back at least 15,000 years, when people traveled there from Beringia, the land bridge now submerged.

Stories nest within stories in this region, or perhaps a better metaphor is that they connect like a chain, in which each link hangs from another. Over the years, I’ve written articles about Nome and the Bering Strait for various magazines and, realizing that there was much more material waiting to be explored, I decided to more fully portray the town and region.

If anything, I’d like readers to acknowledge that this is not an American backwater and never has been, and that history there reaches much deeper than the 1899 gold rush, when “Anvil City,” as Nome was then called, was founded.

Bill Fitzhugh praised the book for “centering Indigenous residents.” How did you make sure their voices and perspectives were represented with accuracy and respect?

As I say in the book’s introduction, I don’t presume to speak for Native peoples but merely about them. To that effect, I have tried to include Native voices, and perspectives, as much as possible and throughout.

As a former anthropologist and longtime guest on Indigenous lands, I have the greatest respect and admiration for the original owners and inhabitants, their resourcefulness, and their ability to adapt to a severe climate and harsh land. I have tried to incorporate (transcribed) sources from oral traditions, which are still underrepresented but just as important as settler history for understanding.

As an anthropologist, I was trained to question the dominant narrative and to seek out alternative paradigms. The fact that the book is being sold at the college in Utqiagvik (formerly Barrow) and at a Native-owned business in Nome tells me that I’ve succeeded to some degree.

Nome has a complex history and identity. What were some of the biggest challenges in capturing that balance of cultures, histories, and humor?

There are groups that literally disappear in the written historical record, leaving hardly a trace: African Americans, Jewish people, Hawaiian whalers, prostitutes, and Alaska Natives, of course, voices that have long been, and still are being, marginalized.

Also, some of the surviving sources must be parsed carefully for biases. Accounts by missionaries, whalers, military men, etc., while containing important information, often paint a skewed, one-sided picture. But I was not interested in a sanitized version of history; I wanted to show some of the racism, as well as some of the unintentional side effects (like epidemics, for example) of colonialism.

I also wanted to entertain, not preach, so I dug deep to unearth some of the bizarre anecdotes and unique characters that the region boasted, and still does.

Can you share a moment or story from the book that, for you, really captures the spirit of Nome?

There are so many that it is hard to choose. But one snapshot that comes to mind is a cold, stormy early summer day when I was beach walking with my wife.

Some Inupiaq kids were out swimming and frolicking, happy as seals amid bergy bits of sea ice. During the 2011 “blizzicane,” I saw kids riding their BMX bikes into rough surf. I really admire that kind of spirit and hardiness.

Nomeites have strange customs, too. After Christmas, people put their trees out on the sea ice (when there is any) and call that the “Nome National Forest.” The town is surrounded by treeless tundra and feels more Arctic than subarctic, culturally and biologically, though it’s at roughly the same latitude as Fairbanks.

You lived in Nome for several years. What experiences during that time most influenced the narrative of the book?

I have a longer history with Northwestern Alaska than just my residence in Nome. As a graduate student, I was involved with a subsistence and land use study in the region (conducted by the National Park Service) and got to visit many remote communities, talking with the elders. That’s when I was first introduced directly to a different worldview.

I’ve also worked as a wilderness guide in northern Alaska and have traversed the Brooks Range from the Canadian border to the Bering Strait, on foot and by raft. So, I think I have a pretty good understanding of the land up there and its inhabitants, though, of course, not nearly as deep as the people born there for generations. But sometimes, an outsider’s perspective can be valuable.

Did you work directly with Nome’s Indigenous community while writing or fact-checking? If so, what was that collaboration like?

The book was largely written after I no longer lived in Nome, and with the multitude of facts, checking each one personally was beyond my reach.

Plus, frankly, there can be ideological divides in Native communities, about conservation versus development, for example, just as in any society. Orally transmitted stories are another good example: different versions usually coexist, so it’s impossible to find the “true” or “official” one.

I tried to double-check the correctness of facts, usually from not one but several sources. UAF’s oral history department has done incredible work interviewing elders and recording them, and I used those archives, plus visual sources (old photos, film clips, etc.).

Nome is often seen from the outside through stereotypes or headlines. What do you think most outsiders misunderstand about the town?

I addressed some of that already, like the lacking depth perception when it comes to the town and region’s human history. Also, for outsiders it’s often just about sled dogs and gold. I tried to show that there’s so much more going on.

I also want visitors to Nome who read the book to understand what they may see and experience there. There is drinking and people sleep on the beach, and there is poverty. I wanted to put that in context (without addressing these things explicitly) and make sure people don’t think, “That’s the culture,” feeding existing stereotypes.

Also, appearances can be deceptive: somebody may drive a truck or have a TV, a modern rifle, and dress “Western” rather than in mukluks and a fur parka, but they still drum dance and believe that polar bears (and other creatures) have powerful spirits.

What role do you see this book playing in conversations about Alaska Native representation and history?

Generally, I’d like people to broaden their horizons, to accept other ways of seeing, doing, and thinking about things. The “American way” is not the only way, the best way, or “the natural way.” If what I write starts a conversation or a reorientation in the reader, I’m doing my job as a writer.

What’s next for you after No Place Like Nome? Are you planning more books?

I have lately developed an interest in contemporary field art, watercolor, pen, ink, and charcoal sketches in journals artists and scientists keep “in the field.” I would like to put together a book including the work of various artists of that genre from northern Alaska, and their perspectives on nature and art.

It’s a highly collaborative project but expensive to produce and somewhat niche. So, I’ll have to secure outside funding, a grant or something, to make that happen with a small publisher or academic press.

If readers visit Nome after reading your book, what’s one thing you’d want them to experience for themselves?

A drumming, singing, and dancing session, especially if they’re lucky enough to catch an AFN (Alaska Federation of Natives) Quyana Night, when dance groups from different villages are in town.

Or go to a potluck at the Nome Community Center. If you can’t make it to Nome, the next best thing would be the World Eskimo-Indian Olympics in Fairbanks in July, they’re not just for tourists.

More Stories Like This

Chickasaw Holiday Art Market Returns to Sulphur on Dec. 6Center for Native Futures Hosts Third Mound Summit on Contemporary Native Arts

Filmmakers Defend ‘You’re No Indian’ After Demand to Halt Screenings

A Native American Heritage Month Playlist You Can Listen to All Year Long

11 Native Actors You Should Know

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher