- Details

- By Kaili Berg

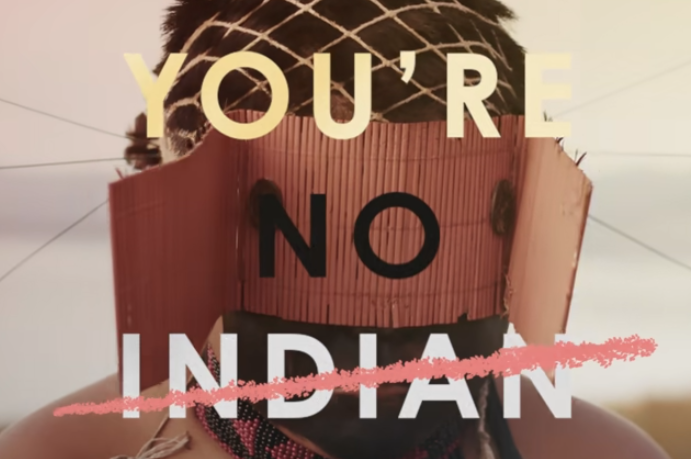

You’re No Indian, a new documentary will premiere on June 28 at the independent Dances With Films Festival in Los Angeles, screening at the historic TCL Chinese Theatre.

Directed by Ryan Flynn, the project represents nearly seven years of immersive reporting into the devastating practice of tribal disenrollment.

Flynn’s journey, sparked by curiosity over casino revenue and Indigenous payouts, led him down a path of deep research, from DNA‑verified family lineages to anthropological evidence, uncovering shocking cases of individuals stripped of tribal citizenship and identity.

The documentary exposes a hidden crisis, one that has affected an estimated 11,000 tribal members across 80 tribes in the last 15 years, and also offers intimate storytelling that bridges personal anguish and political power plays.

The film is executive produced by Wes Studi and Tantoo Cardinal, with Cardinal lending her voice as narrator and Studi guiding the film’s development and messaging.

Native News Online spoke with Flynn about the issue of tribal disenrollment, the emotional impact of documenting it, and how the film evolved with support from Wes Studi and Tantoo Cardinal.

The June 28 premiere includes ticket pickup starting at 1 p.m. outside the Chinese Theatre. An encore screening will follow on Sunday, June 29, with tickets available for purchase online.

Attendees are encouraged to show their support by wearing YNI merchandise, with all proceeds supporting broader distribution of the film.

This interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

How did your perspective evolve during the filmmaking process?

The way I came across this story, I have a propensity to Google things. One evening I was just curious and went down a rabbit hole: “How much does an Indigenous person get from their casinos?”

And the answer I found was, it changes tribe to tribe. Sometimes it’s nothing. Sometimes I found one that was over $100,000 a month.

That’s how I came across the concept of disenrollment. People were claiming they were rightful members and were being kicked out. I looked for a documentary about it, and it wasn’t there. So I started speaking with people, looking at their evidence, and it looked good.

I spoke with an anthropologist, and it looked good. Then we went all the way to speak with the scientists who did DNA tests on exhumed individuals. They passed the tests, and were still kicked out.

It sounded like an important story that no one was talking about. I was shocked that I didn’t know. And that’s been the reaction, even from Indigenous people. Some don’t know this is happening.

For those unfamiliar with disenrollment, your film offers a rare, intimate lens into its impacts. What do you hope audiences, both within and outside of Indian Country, walk away with after watching it?

There’s a lot I want people to take away. One is that there are leaders and there are politicians. Leaders operate in the best interest of their people. They grow their tribes, they make them better.

Politicians work for themselves. That’s where we see people getting kicked out, because the fewer members in the tribe, the bigger piece of the pie someone gets, whether it’s gaming money or something else.

We have to spotlight these politicians so that future ones, when thinking about doing this, think twice, knowing the public is aware. That whole “it’s an internal matter” mantra starts to lose its power.

The title You Are Not Indian is powerful. Talk about the choice behind it and how it reflects the experiences in the film?

We were looking for a title. Banished was one of them. But “banished” implies you can come back. It doesn’t necessarily affect your children or your grandchildren. We also looked into words for “kinship” in different Native languages.

And then one day, it just occurred to us, because we heard people say it: “You’re no Indian.” It’s wrong. It’s wrong in many ways. It’s wrong to say they are Indians, and it’s wrong to say they’re not. That phrase really embodies what this film is about, people wrongfully having their heritage stripped from them for greed.

You worked with Wes Studi and Tantoo Cardinal as executive producers. How did their involvement shape the film’s message?

It’s an honor to have both Wes Studi and Tantoo Cardinal on board. This isn’t just name involvement. They played significant roles. Tantoo narrated the film herself. Wes has been a guide, giving notes on different versions of the film, there’s a lot of his perspective in it.

When I first met him, I don’t want to speak for him, but he seemed unaware of the scale of the issue. And we believe this is just the beginning. Disenrollment can affect any tribe. It’s an existential threat to nationhood itself.

When Wes saw the film, he called me and said, “If you think it can help, I’m in.” And it has.

Was there a moment during production that crystallized the stakes of this issue for you, personally or artistically?

That’s difficult to talk about. We do go into suicidal thoughts, what happens when you lose your identity. If you’ve grown up Indigenous your whole life and then you’re disenrolled, who are you? What are you?

I was surprised by how often this came up. People I’ve known for years, when I sat them down and asked, it was so prominent. One man looked me in the eye, started crying, and opened up to me about those kinds of thoughts.

That profoundly showed me the weight of this issue. It’s not just about money. It’s the loss of identity, the destruction of heritage, language, culture.

We follow people who are the last language speakers in their communities, and who stood up against disenrollment. They shut down the language school and fired him. The weight of this is profound. Like I said, it’s an existential threat to all Indigenous nations.

Now that the film is premiering at Dances With Films at the Chinese Theatre in Hollywood, what are your hopes for where it goes next? Public dialogue? Policy change?

It’s awareness. I think people just don’t know about this. And if they do, they’ll care. Indigenous history is human history. It’s part of our story as U.S. citizens, the good and the bad.

If people knew what was happening, what the UN calls human rights violations, they would care. And if they care, action can happen. Maybe that means not going to casinos that disenroll their people. Being allies to those who’ve been disenrolled.

There’s also the weaponization of fear. People are afraid to speak out, afraid they’ll be targeted. And there’s the weaponization of hope. If you’ve been disenrolled but keep your head down, maybe you’ll be let back in.

I’m hoping this conversation, happening at a national or international level, gives people the courage to speak out. Disenrollment lives in the shadows. If we talk about it, it can’t.

How has the response been from tribal communities or governments? Has any of it surprised you?

Tears. From the number of Indigenous people we’ve shown this to, it’s been across the board. Tears. That’s powerful.

My job as the director is to take the voices of people who were brave enough to speak with us and make them louder. This is their story.

In documenting disenrollment, did you find any moments of resistance or hope that really stood out, either in others or in yourself?

There are leaders. People who fight, at great personal expense, because it’s the right thing to do. You can say you’re thinking seven generations back and seven generations forward, but we met people who actually do that.

We celebrate those leaders. The ones preserving language, culture, tradition. And we spotlight those who are attacking it.

More Stories Like This

A Native American Heritage Month Playlist You Can Listen to All Year Long11 Native Actors You Should Know

Five Native American Films You Should Watch This Thanksgiving Weekend

Heavy metal is healing teens on the Blackfeet Nation

Over 150 Tribal Museums Participate in Fourth Annual Celebration of Native Life

Help us tell the stories that could save Native languages and food traditions

At a critical moment for Indian Country, Native News Online is embarking on our most ambitious reporting project yet: "Cultivating Culture," a three-year investigation into two forces shaping Native community survival—food sovereignty and language revitalization.

The devastating impact of COVID-19 accelerated the loss of Native elders and with them, irreplaceable cultural knowledge. Yet across tribal communities, innovative leaders are fighting back, reclaiming traditional food systems and breathing new life into Native languages. These aren't just cultural preservation efforts—they're powerful pathways to community health, healing, and resilience.

Our dedicated reporting team will spend three years documenting these stories through on-the-ground reporting in 18 tribal communities, producing over 200 in-depth stories, 18 podcast episodes, and multimedia content that amplifies Indigenous voices. We'll show policymakers, funders, and allies how cultural restoration directly impacts physical and mental wellness while celebrating successful models of sovereignty and self-determination.

This isn't corporate media parachuting into Indian Country for a quick story. This is sustained, relationship-based journalism by Native reporters who understand these communities. It's "Warrior Journalism"—fearless reporting that serves the 5.5 million readers who depend on us for news that mainstream media often ignores.

We need your help right now. While we've secured partial funding, we're still $450,000 short of our three-year budget. Our immediate goal is $25,000 this month to keep this critical work moving forward—funding reporter salaries, travel to remote communities, photography, and the deep reporting these stories deserve.

Every dollar directly supports Indigenous journalists telling Indigenous stories. Whether it's $5 or $50, your contribution ensures these vital narratives of resilience, innovation, and hope don't disappear into silence.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Native languages are being lost at an alarming rate. Food insecurity plagues many tribal communities. But solutions are emerging, and these stories need to be told.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Native languages are being lost at an alarming rate. Food insecurity plagues many tribal communities. But solutions are emerging, and these stories need to be told.

Support independent Native journalism. Fund the stories that matter.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher