- Details

- By Neely Bardwell

As the November 5 presidential election gets closer, both Democrat and Republican candidates are increasing the number of campaign appearances in pivotal states considered key to victory, including Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, North Carolina, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin.

Indian Country says they matter, too.

In 2020, the Native vote helped secure the win for President Joe Biden, as Native Americans turned out in record numbers to the polls. Voters in precincts on the Navajo and Hopi reservations in northeastern Arizona cast nearly 60,000 ballots in the Nov. 3 election, an increase from 42,500 in 2016. Biden won Arizona by about 10,500 votes, according to unofficial results. Turnout in two of the larger precincts on the reservations rose by 12% and 13%.

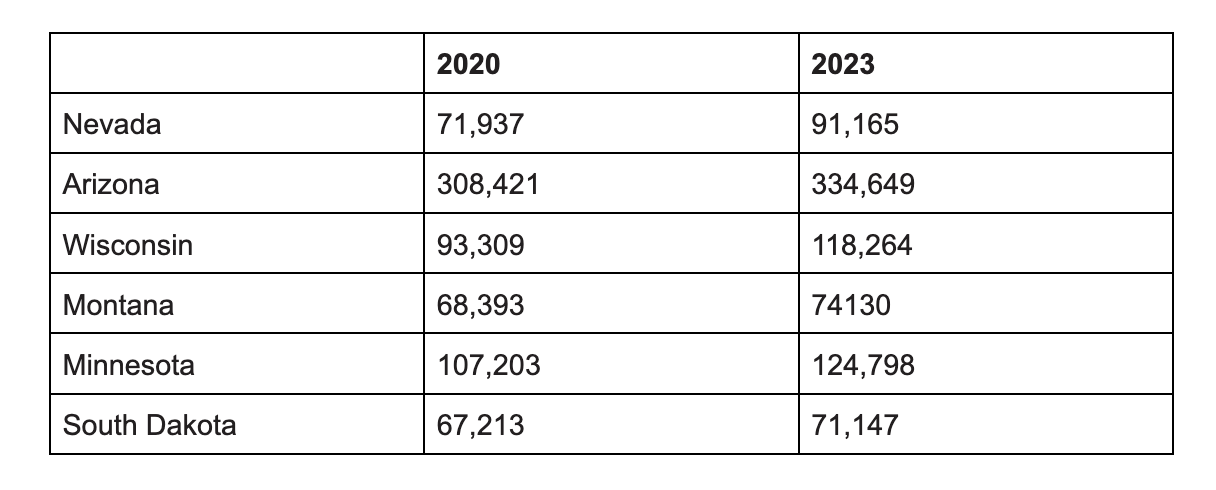

Across the country, Arizona, Alaska, Oklahoma, New Mexico, South Dakota and Montana have the highest percentages of Native Americans eligible to vote, according to the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI). In Arizona, that was about 310,000 potential presidential votes in 2020. Now, the number of eligible Native voters has risen in some key battleground states.

Number of Eligible Native Voters in Battleground States

An open letter signed by Chair Brenda Meade of the Coquille Indian Tribe, Chairman Marshall Pierite of the Tunica-Biloxi Tribe of Louisiana, and Chair Brad Kneaper of the Confederated Tribes of Coos, Lower Umpqua and Siuslaw Indians, was sent on September 30 to presidential candidates, debate moderators, consultants, political commentators, and the media stressing the importance of Native issues being discussed in politics.

“As we approach the election, it is crucial that presidential candidates do not ignore Indian Country and can articulate their positions to voters nationwide. Though there are nearly 10 million Native Americans who have the power to impact politics and elections, our rights and needs are rarely at the forefront of national conversations,” the letter reads.

They go on to list several key issues that candidates could address on the presidential debate stage, including treaty rights, health, elder care, education, housing, and the protection of the environment and natural resources.

“We ask moderators to take a bold step forward and put Native issues on the presidential debate stage,” the letter stated.

NCAI held a series of webinars this past month focused on the importance of Native American voter participation. The series is part of NCAI’s non-partisan national Native Get Out The Vote (GOTV) Campaign.

During the Midwest, Northeast, and Southeast Regions webinar on August 28, presenters Dr. Aaron Payment, NCAI Get Out The Vote Campaign manager, and NCAI Executive Director, Larry Wright Jr. (Ponca Tribe), shared statistics showing just how powerful the Native vote can be.

“Yes, Your vote matters. President Kennedy won his election in 1961 by just over 100,000 votes, or an average of one vote per precinct. The 2016 presidential election in Michigan was decided by just over 10,000 votes. The number of Native Americans in Michigan in 2020 is about 110,000. We can be the margin of victory,” Payment explained.

In 2016, the margin of victory was 3.7 percent in North Carolina. The percentage of the Native population in North Carolina is 3.9 percent. In Arizona, the margin of victory was 4.1 percent, and the Native population is around 15.8 percent. These trends continue in Michigan, Nevada, and Wisconsin.

“If you vote in favor of candidates who have a platform supporting the treaty and trust obligations, you strengthen our sovereignty,” Payment said during the webinar. “If you prioritize the impact of the federal government on our tribal sovereignty and federal funding as Indians, we win. Who you vote for is entirely up to you. You are encouraged, however, to research the candidates and ask the tough questions of how they will serve you as an American Indian.”

NCAI is compiling a list of priorities for Indian Country that candidates should know dubbed a “sovereignty ticket.” Elected officials hold a unique obligation to uphold treaties and trust obligations the federal government has for tribal nations, but how can these campaigns break into Indian Country?

OJ Semans Sr., Executive Director of Four Directions, a non-partisan voting rights advocacy group, says outreach to inter-tribal organizations is key.

“They can reach out to tribal organizations. You have the Great Lakes Intertribal Council that has contact with every tribal leader in Michigan and in Wisconsin. You have the Mid-Western Alliance that covers Minnesota and a lot of tribes. You have the Great Plains Tribal Chairman's Association. We have tribes in almost every state,” Semans Sr. said. “But the simplest way for them to do it would be to work within the Native Caucus, within their own organization, to reach out to tribal leaders. It's so simple. You have so many well-known Natives within the Native Caucus and Democratic Party that they could call anybody in any tribe in the United States, and the phone would be answered.”

Winning the Native vote could clinch the win for either candidate, but campaigns have to do the work.

“It is very critical that they [campaigns] are able to relay their message to tribes and the Native voting population that they're aware of how important we are, because we can, and we have, from the election of President Biden and Vice President Harris have shown that power that vote,” Semans Sr. said.

More Stories Like This

Native News Weekly (August 25, 2024): D.C. BriefsUS Presidents in Their Own Words Concerning American Indians

Two Murdered on Colville Indian Reservation

NDAA passes House; Lumbee Fairness Act Advances

NFL, Vikings to Host Native All-American Game, Youth Flag Clinic

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher