- Details

- By Native StoryLab

In 1945, the U.S. government detonated the first-ever nuclear bomb in the New Mexico desert. But while history books focus on the birth of the atomic age, they largely ignore the slow, invisible war it unleashed on the people living nearby, many of them Indigenous.

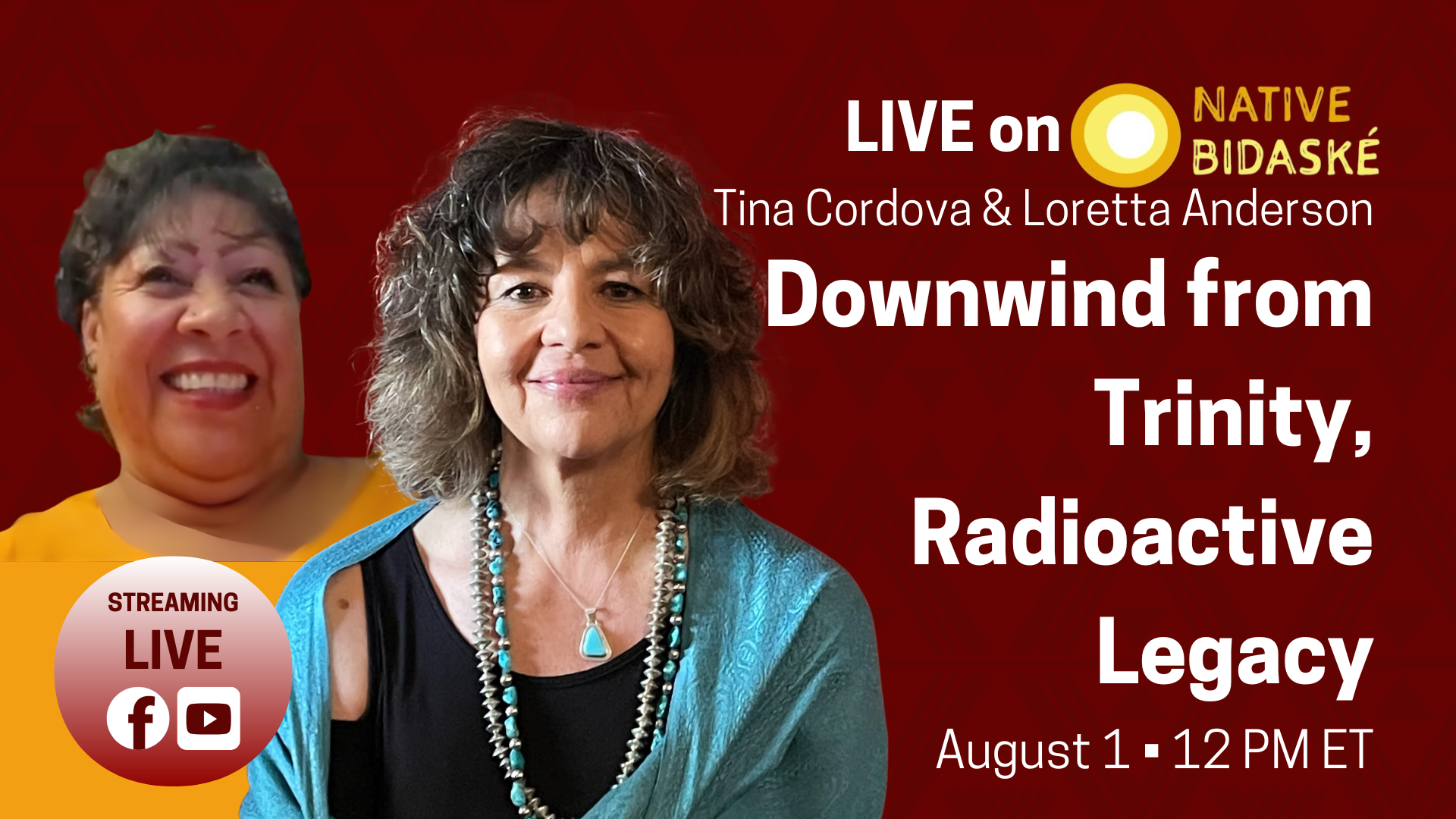

On the latest episode of Native Bidaské, host Levi Rickert sat down with Tina Cordova and Loretta Anderson, two women who’ve spent decades fighting for justice for uranium workers, downwind families, and Native communities poisoned by America’s nuclear legacy. Their stories reveal an 80-year pattern of exposure, illness, loss, and now, the first glimmers of overdue compensation.

Tina Cordova, co-founder of the Tularosa Basin Downwinders Consortium, has spent 20 years documenting the impact of radioactive fallout on New Mexico families. She’s the fourth generation in her family to be diagnosed with cancer since the Trinity Test. “Almost 100% of my immediate family has had cancer,” she told Bidaské viewers. “And my family’s not unique.”

Her coalition has uncovered data showing a dramatic rise in infant deaths after the Trinity detonation, jumping from 30 to over 100 deaths per 1,000 births that summer alone. The U.S. government never warned residents, never cleaned up the contamination, and never returned to assess the damage. “They didn’t want to see us, so they didn’t see us,” Cordova said.

Loretta Anderson, of the Pueblo of Laguna, has seen the same story unfold around uranium mines. She co-founded the Southwest Uranium Miners Coalition to support miners, many Native, who were exposed with little protection and even less information. “Our people are sick. Our children are being diagnosed with cancer. We mourn every week,” she said. “And our lands, air, and water are still contaminated.”

Both women spoke of the generational grief, loss, and injustice their communities continue to face. “Money can’t buy life,” Anderson said. “I’d give anything to have my father back. He died of cancer from working in the mines. My mother worked in the office at the mine and developed pulmonary fibrosis. She doesn’t even qualify for compensation.”

For decades, the federal government has offered limited assistance under the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA), but left out post-1971 uranium workers and most downwind communities in New Mexico. That changed last month when President Trump signed a provision in the federal budget extending RECA by two years and expanding eligibility. The new $8 billion package includes:

- Coverage for uranium miners and workers expanded

- $100,000 payments for qualifying downwinders

- Downwinders who lived in New Mexico for one year from 1944 through Nov. 1962 will be eligible, and family members can apply on behalf of a deceased loved one

More information on the expansion to RECA is summarized here.

While it's a step forward, Cordova calls it “a pittance” compared to the nearly $10 trillion spent on nuclear development. “We wanted health care coverage for all downwinders,” she said. “They stripped that out, saying it would cost too much.”

Anderson added, “Now that money’s coming, the scammers are too. Our coalition is shifting focus; we’re training people to help communities file claims properly. No one should have to pay an attorney to get what they deserve.”

Both women emphasized the urgency of educating communities, especially with uranium mining and nuclear testing on the rise again. “They counted on us to be uneducated and unable to speak up in the 1940s. We’re not those people anymore,” Cordova said. “We’ve borne our share. We won’t be collateral damage again.”

To learn more or get help with the claims process, visit: www.trinitydownwinders.com

🎥 Watch the full Native Bidaské episode here:

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher