- Details

- By Chez Oxendine

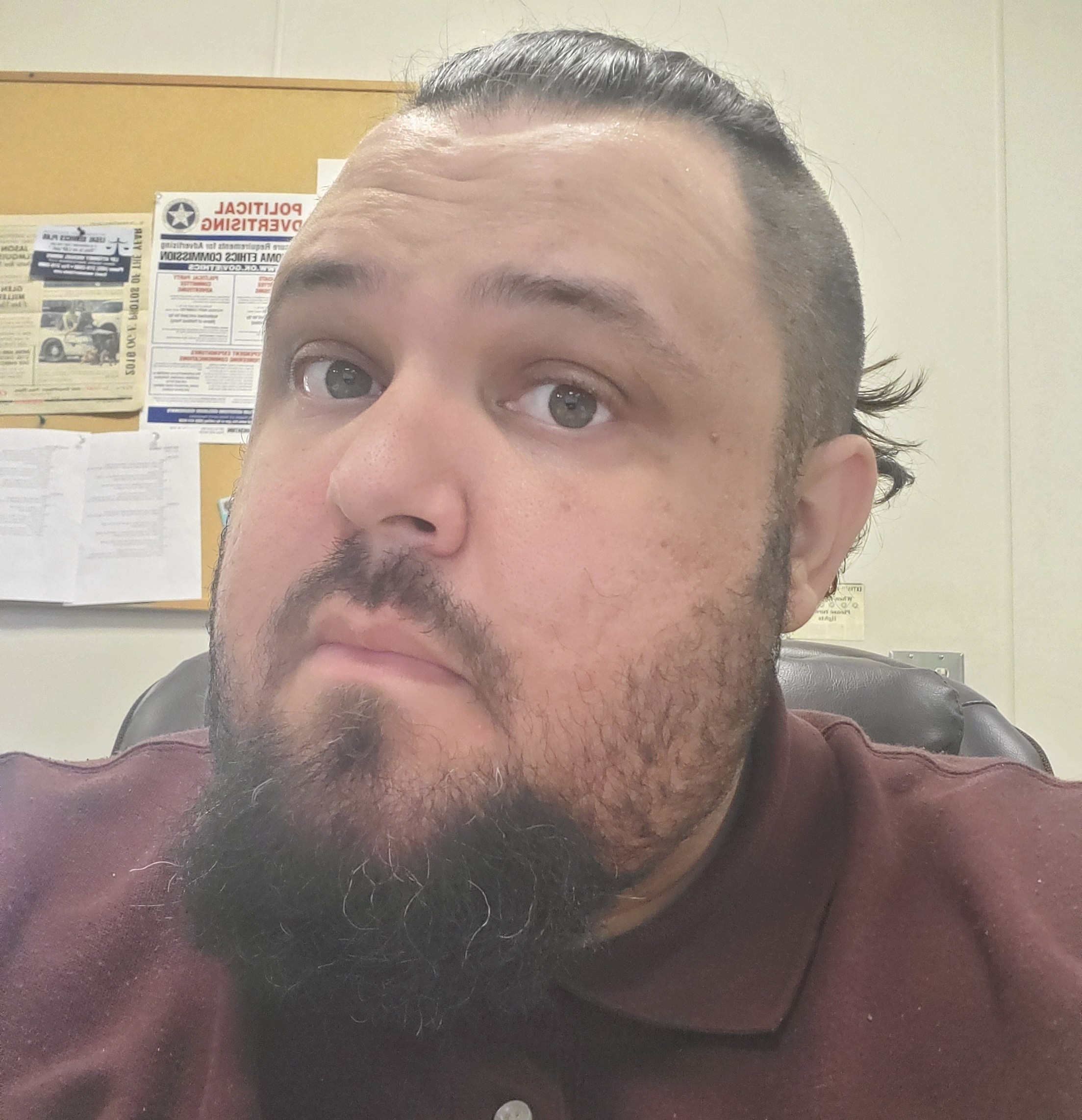

The Kiowa Tribe of Oklahoma is mourning the loss of tribal elder, historian, and advocate Dr. Phil “Joe Fish” Dupoint, who walked on Jan. 2 at the age of 70

Born Jan. 25, 1954 to Joseph and Georgia Dupoint in Anadarko, Okla., Dupoint was raised by his grandmother, Celia Maude Hainta. As a direct descendent of Kiowa chiefs Sate-T’hai-Day and Ahpeahtone, Dupoint dedicated his life to learning and sharing the Kiowa culture, chronicling the tribe’s history, fighting to preserve its traditions and land, and educating younger generations.

In a 2013 interview with documentarian Philip Bally, Dupoint said his traditions were central to his identity — the touchstone to which he returned again and again.

“I love being a part of it…I do the best I can to uphold my traditions and my culture, because the only thing I can say is that God Almighty made me who I am,” Dupoint said. “He made me a Kiowa. He didn’t make me nothing else. So I love my traditions as a Kiowa. I love them.”

Dupoint leaves behind him a legacy of cultural preservation, education, and celebration. At the time of his passing, he worked as a historian for the Kiowa Tribe, following his role as a project coordinator for the Kiowa Language Program. He shared his heritage across the country with his drum group, Bad Medicine.

Dupoint was also a member of the Kiowa Native American Church, headsman for the Kiowa Gourd Clan, and the principal singer for the Kiowa Black Leggings Society. In 2020, he received an Honorary Doctorate of Humane Letters for his contribution to the Kiowa culture.

“Bacone College recognizes Phil “Joe Fish” Dupoint as a cultural treasure of the Kiowa people. His eminent knowledge, experience, and expertise of Kiowa history, culture, language, philosophy, and ceremonies deem him an important and valuable Indigenous scholar, teacher, and leader,” Dr. Ferlin Clark, then-president of the school, said in a press release. “He has made a lifetime contribution to the cultural, spiritual, and ceremonial health and well-being of the Kiowa people for many generations.”

Dupoint is survived by his daughter, Karita Ramos; his son, Harold Neconie; Phyllis Whitecloud and son Gary Whitecloud, Jr.; as well as his sisters Loretta Scantlen, Lela Cozad, Cheryl Gouge, Carrie "Chickie" Whitebuffalo, Franda Flyingman and Charlotte Lomayasva.

He is also survived by his fellow Bad Medicine musicians Alan Yeahquo, Cletis Gayton, Steve Bohay, James Tofpi, and Gene Ray Ahboah, as well as his aunts Francis Bailey and Agnes Hiney, uncle Cletis Septuahoodle, a host of nieces and nephews and grandchildren, and the extended relationships he forged throughout Indian Country.

Dupoint was preceded in death by his parents, Joseph and Georgia Dupoint; daughter, Cara Lynn Dupoint; grandparents, Herbert Topoie Dupoint and Cecelia Maude (Hainta Mah); his aunts Pearl Woodard and Ida Kaubin, uncle Raymond Whitebuffalo, sisters Marilyn Darlene, Hazel Celia, Sheila Ann, and Christina Sue, Lena Kaulaity, and Allene Woodard, and brothers Donald Earl Dupoint, Phil Bohay, George Botone, Marquis Woodard, Allen Woodard, Thomas Woodard, Tony Isaacs and Gerald "Skippy" Kaudlekaule Grandson Phillip Autaubo, and the love of his life, Joyce Ann Dupoint.

Dupoint’s funeral was held Tuesday, Jan. 7, at Red Wolf Hall in Carnegie, Oklahoma.

More Stories Like This

Native News Weekly (August 25, 2024): D.C. BriefsScope Narrowed, Report Withheld: Questions Mount Over Michigan Boarding School Study

Zuni Youth Enrichment Project Announces Family Engagement Night and Spring Break Youth Programming

Next on Native Bidaské: Leonard Peltier Reflects on His First Year After Prison

Deb Haaland Rolls Out Affordability Agenda in Albuquerque

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher