- Details

- By Levi Rickert and Neely Bardwell

Editor’s Note: This story was published in observance of Orange Shirt Day in 2021. Native News Online is republishing it again this year.

Phyllis Webstad, a tribal citizen of the Stswecem’c Xgat’tem First Nation, is a prime example of how one person can make a difference and create an Indigenous movement across North America.

Webstad is the force behind the Orange Shirt Day movement that is commemorated each year on Sept. 30 to remember Indigenous people who attended Indian residential schools in Canada and Indian boarding schools in the United States.

Want more Native News? Get the free daily newsletter today.

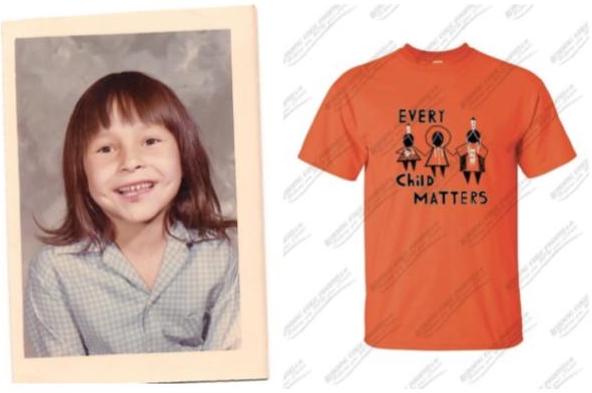

The color orange was chosen because of something that happened to Webstad when she was only six years old. It was Sept. 30, 1973, the first day she attended St. Joseph’s Mission Residential School in British Columbia. Her grandmother had bought Webstad a brand-new shiny orange shirt to wear, adding to the young student’s first-day-of-school excitement.

Unfortunately, when Webstad got to school, the orange shirt was taken from her, and it was never given back.

“I didn’t understand why they wouldn’t give it back to me, it was mine! The color orange has always reminded me of that and how my feelings didn’t matter, how no one cared and how I felt like I was worth nothing. All of us little children were crying, and no one cared,” Webstad said.

She never forgot the loss that turned into a hurt to her heart.

In 2013, Webstad was asked to return to St. Joseph’s as an Indian residential school survivor. She convinced other survivors to buy orange t-shirts as a way to remember those who attended the residential schools in Canada. She formed the Orange Shirt Society.

“Wearing orange shirts are a symbol of defiance against those things that undermine children’s self-esteem, and of our commitment to anti-racism and anti-bullying in general,” Webstad explains.

The Orange Shirt Society is not all about defiance though.

“Orange Shirt Day is also an opportunity for First Nations, local governments, schools and communities to come together in the spirit of reconciliation and hope for generations of children to come,” Webstad said.

September 30 was chosen as the primary day of remembrance because it is around that time of the year that Indigenous children were taken from their homes and sent to residential schools. It was also chosen because “it is an opportunity to set the stage for anti-racism and anti-bullying policies for the coming school year,” Webstad explains.

Since 2013, the Orange Shirt Day has morphed into days of reflection throughout Canada and the United States. Orange has become a color for women jingle dress dancers.

Today’s Orange Shirt Day has a more serious tone, following the revelation in late May that the remains of 215 children were discovered in a mass grave at the former Kamloops Indian Residential School. Since then, thousands of other bodies have been found at residential schools throughout Canada.

“Every child matters” has become a mantra for t-shirts and rally signs.

This year, for the first time, Canada will celebrate Truth and Reconciliation Day. But to many, Sept. 30 will always be known as Orange Shirt Day because of the difference Phyllis Webstad made in the creation of an Indigenous movement.

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher