- Details

- By Native News Online Staff

Tribal nations in the United States are leading a “Rights of Nature” movement to enshrine the inherent rights of the natural world — including plants, animals, and lands and waters — into law.

Last week, the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians in northern Michigan passed a resolution in defense of the tribe’s first family: its natural resources.

“Anishinaabe izhitwaawin, ways of thinking and being, includes a decentralized view of human beings who are not on top of an evolutionary hierarchy, but rather dependent upon the older wiser More Than Human Relatives that our first ancestral family created before the human beings,” the resolution reads.

Further, the tribe says it “recognize[s] that to protect our more than human relatives and our people, we must secure highest protection through the recognition of legal rights, and call upon the bands of the Anishinaabeg Nation, and other relevant federations, commissions, and government entities, to secure and protect the legal rights of More Than Human Relatives and our peoples.”

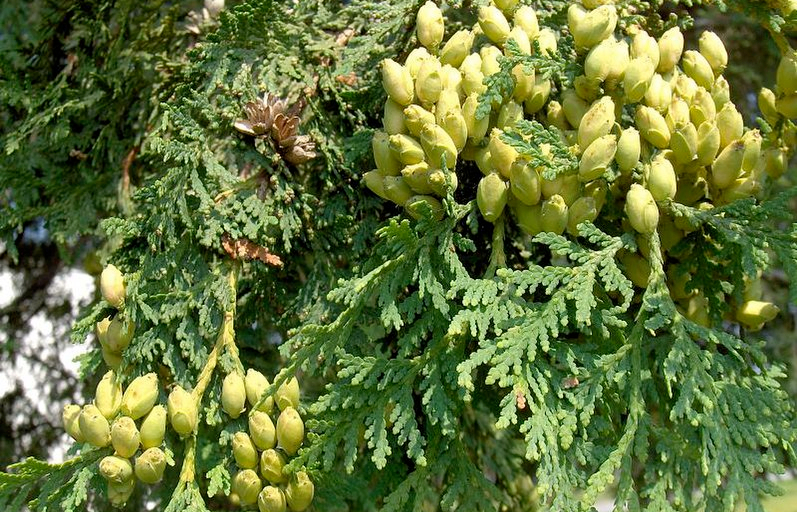

This action builds on groundwork the tribe has already done. In February 2024 the tribe updated its code to protect Giizhik trees, sacred beings in Anishinaabe culture, from overharvest. Under the new law, tribal members must obtain a permit before collecting Giizhik bark from tribal or public land. Legal harvesting under the updated code is designed to protect and honor Giizhik trees and to maintain good harvesting relationships in future generations, according to the tribe.

“From extractive mining and forestry practices to the harmful use of pesticides and chemicals on the land to the destruction of our sacred rapids for the shipping industry that caused the introduction of invasive species into the Great Lakes, our people have witnessed generations of injury to our More Than Human Relatives,” Sault Tribe Chair Austin Lowes said in a statement. “This resolution reaffirms our commitment to our shared dependence with them and to honoring our ancestors by always making decisions with the next seven generations of both human and nonhuman beings in mind.”

The work of adopting legal frameworks that recognize and defend the rights of nature is growing throughout tribal nations. In February, a Native-led group, Bioneers, published a guidebook that provides strategy and resources for Indigenous communities interested in enacting their own laws granting ecosystems, landscapes and species legal rights and personhood.

Rights of Nature laws aim to protect nature by recognizing a natural entity’s legal rights and granting natural entities “legal personhood.” The rules can be made legal through tribal ordinances, tribal resolutions, and constitutional amendments, according to the guide.

More than half a dozen tribes have enacted such laws since 2017, including the Ho-Chunk Nation, which added the Rights of Nature to their constitution in 2016, and the Ponca Tribe of Nebraska, which passed a similar resolution the following year to address problems caused by fracking nearby and on the tribe’s reservation.

Three tribes have passed resolutions giving rights to their rivers. The Yurok established the Rights of the Klamath River in 2019. The Nez Perce gave rights to the Snake River in 2020; and the Menominee Indian Tribe of Wisconsin enshrined rights to the Menominee River in 2020.

In 2022, the Sauk-Suiattle Indian Tribe in Washington state brought a lawsuit against the city of Seattle, naming salmon as the plaintiff. The case alleged that river damming infringed on the ‘inherent right to exist’ of the fish. The lawsuit resulted in the city of Seattle settling and agreeing to include fish passages in any new permit or permit renewal for hydro dams.

More Stories Like This

Rappahannock Tribe Challenges 9M-Gallon Water PlanFeds release draft long-term plans for Colorado River management

Apache Leader Walks 60 Miles to Court Hearing That Will Decide Fate of Sacred Oak Flat

Rappahannock Tribe Raises Sovereignty and Environmental Concerns Over Caroline County Water Permit

Klamath Indigenous Land Trust Purchases 10,000 Acres as Salmon Return

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher