- Details

- By Elyse Wild

Despite Indian Country bearing some of the highest fatality rates of the overdose crisis, there is a woefully insufficient number of programs that provide clean needles in Indian Country to reduce death and the spread of disease.

That's according to a report published in the Harm Reduction Journal that examined the state of tribally-run syringe service programs (SSPs), which provide sterile injection supplies for intravenous drug users. SSPs, sometimes referred to as needle exchanges, are an evidence-based public health measure that has been proven to reduce death and infectious disease. Across Indian Country’s 575 federally recognized tribes, there are 21 tribally run SSPs.

With less than 5% of tribes having access to a critical harm reduction measure, the unmet need for culturally appropriate services is vast and potentially costing lives.

Brief History of a Crisis

Now in its fourth wave, the overdose crisis was once driven by the overprescription of opioid painkillers, such as OxyContin and Tramadol. Today it is characterized by fentanyl, a synthetic opioid 50 times stronger than morphine, being mixed into non-opioid drugs, such as methamphetamine, cocaine and ecstasy, driving up overdoses in non-opioid addicted drug users. In 2023, more than 106,000 Americans died from drug overdoses, according to CDC data.

While Americans of all races and ethnicities have been affected, the crisis is especially prevalent in Indian Country. Native Americans have the highest rate of drug-overdose deaths of any ethnic group. It reached 65.2 per 100,000 people in 2022, 15% more than in 2021, according to CDC data. While 2024 saw the largest decrease in overdoses among the general population, they remain high among AI/AN.

As well, Native people have the highest rates of acute hepatitis C infection, with HIV diagnoses linked to injection drug use increasing 71% from 2018 to 2022.

The Challenges

Many tribes have embraced harm reduction as a measure to help relatives heal from the overdose crisis. While most harm reduction programs provide overdose reversal drug Nalaxone, not all include SSPs, although there is a high demand for them. The study notes that 56-98% of Indigenous people who use drugs express willingness to use SSP services if they are available.

Even though syringe services are still shrouded in stigma that they encourage drug use, according to the CDC, people who use needle-exchange programs are five times more likely to enter drug-treatment programs and 3.5 times more likely to stop injecting drugs.

Meeting the need for addiction care and harm reduction services is a big lift for many tribes. Challenges not only lie in accessing funds, navigating jurisdictional layers, and training qualified staff, but also in stigma, burnout, strained resources, and community buy-in.

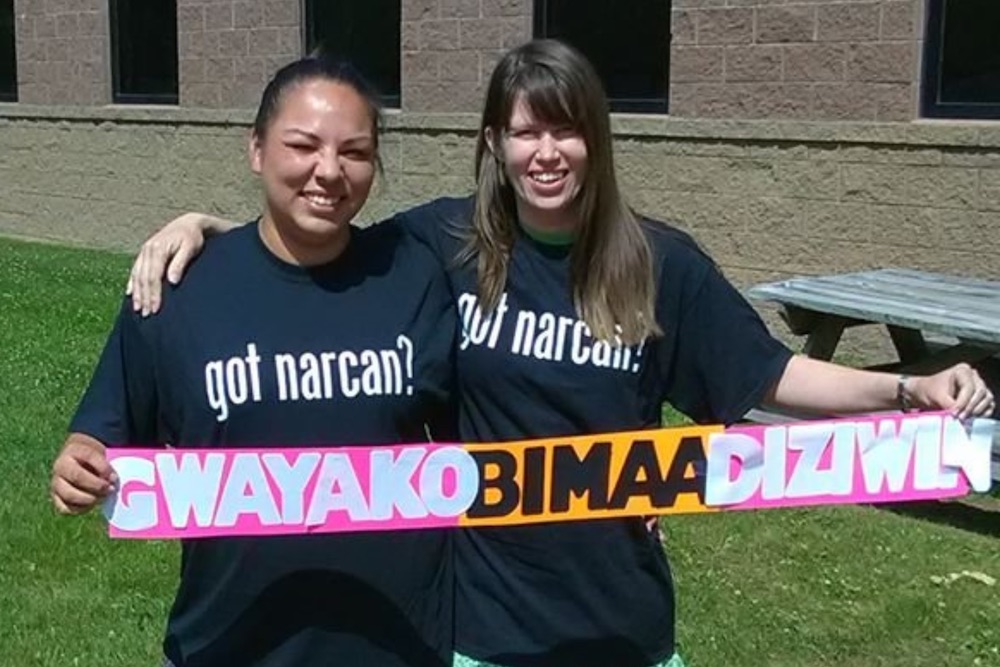

Philomena Kebec (Bad River Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians), one of the report's co-authors, had first-hand experience in running a tribal syringe program. Kebec is an attorney and fellow at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and the founder of the Gwayakobimaadiziwin Bad River Harm Reduction Program. She spoke to Native News Online about challenging the stigmas that limit service to drug users in tribal communities.

"There has been a deep-seated concern about how people who use drugs in our communities — that's a shameful activity, and it reflects negatively on our entire community," Kebec said. "There are a lot of tropes about drunken Indians, drug-rattled Indians and there can be a desire to protect our outward image. It becomes a question of how do we maintain a positive self-image as a community and also interact with people who use drugs in our community in a humane way? I think there is tension there."

Healing

Kebec says that maybe successful tribal SSPs tend to start as grassroots efforts spearheaded by tribal citizens — starting from the community level, as opposed to the tribal council, or top down.

“That is a more effective starting point than leadership coming to a group of employees and saying, 'You need to do this now,'" she reflected.

Kebec and her partners started the Gwayakobimaadiziwin Bad River Harm Reduction Program in 2015 with a needle exchange out of her garage. In Wisconsin, where the Bad River’s lands are located, Native people die of overdoses three times higher than the national average.

In 2023, the Gwayakobimaadiziwin received more than 100 returned batches; distributed over 8,000 doses of naloxone and 100,000 syringes, collected 300 pounds of syringe waste, mailed 1,400 harm-reduction kits, and made over 2,000 face-to-face contacts, according to an article by State News. Through a partnership with harm reduction service NEXT Distro, Gwayakobimaadiziwin is the largest distributor of free Naloxone in the state of Wisconsin.

The report published in the Harm Reduction Journal underscores what Native communities already know: culturally-centered care and traditional healing practices paired with addiction medicine increase positive outcomes for treatment. For many communities, Kebec said, harm reduction is an extension of traditional values.

"We have culture and language and things that all connect us, and we have a wicked sense of humor," Kebec said. "We have so many different types of common language and things that connect us. We have a responsibility to each other. As harm reductionists, we translate the work that we do in terms of the values of our tribal community."

The benefits of culturally centered harm reduction services extend beyond those being served. With such a high demand for services, tribal harm reduction staff who work face-to-face with the community, many of whom could be direct relatives, can experience high levels of stress and even trauma.

"We're constantly in this place where we're trying to evaluate workload and stress, and balancing the need for people to have immediate services with the need for my staff to have a break," she said. “We try to have a ceremony here as often as we can. We're integrated into the community. That’s part of the theory that we're trying to examine: how does incorporating traditional medicine into harm reduction improve the lives of the people that we serve? And then, how does it help address the workplace stress and trauma that all my workers experience? That's why traditional medicine is so nice, because it provides this opportunity to do really positive things for the whole community. Everybody gets healing from it.”

More Stories Like This

Office on Violence Against Women Government-to-Government Tribal Consultation Set for Jan. 21 - 23 at Mystic LakeBREAKING: Feds Reverse $2B in Cuts to Addiction, Mental Health; Native Programs Restored

Trump Administration Cuts End Five Indigenous Health Programs at Johns Hopkins

Navajo MMDR Task Force Addresses Gaps in Missing Persons Cases, Strengthens Alerts

Tribe Sues IHS Over Rejected Opioid Treatment Facility as Natives See Highest Overdose Rates