- Details

- By Joshua Arce

When news broke of the 215 bodies of Native American children found on the grounds of a former Canadian residential boarding school, my heart sank. It was like an earthquake shifting deep inside and causing a reverberation throughout my entire being. The historical trauma of the boarding school era hits deep, and while this particular school was in Canada, boarding schools throughout North America were highly detrimental, generationally damaging and wholly destructive to Native American tribes.

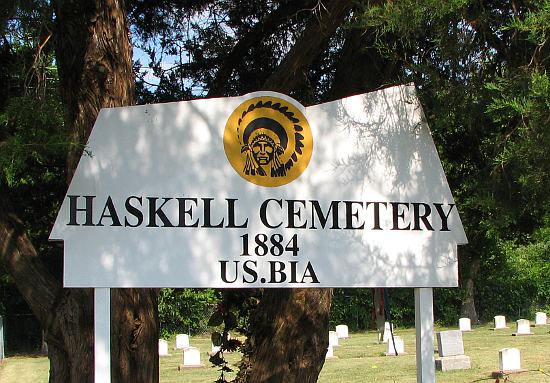

It took me some time to process the news. Even as someone who is somewhat desensitized to this kind of history—having attended and worked at Haskell Indian Nations University where there is a cemetery with 100 graves from the boarding school era—I was speechless. For some reason, this resonated with me and I think it was because of all the chatter I saw about it. The reality is that few people know of this dark chapter in U.S. history.

Want more Native News? Get the free daily newsletter today.

When I talked with my mother about the discovery and our own ancestors’ experiences with boarding schools, she wept. She has a 5-year-old granddaughter and her heart absolutely breaks for the families who were impacted by the atrocities of the boarding school era. We talked about my grandmother, Etheleen, and great-grandmother, Lillian, both of whom went to boarding school as children and how this impacted our family.

Like me, my grandmother attended Haskell, which was originally founded as an industrial training school and one of several Indian boarding schools in the Midwest. She wanted to be an accountant but, at the time, the school did not allow women the same educational opportunities as men. Instead, she was relegated to domestic and clerical work. Similarly, my great grandmother attended Chilocco Indian School in Oklahoma in the early 1900s. She passed away when I was 5 and I can only recall a few interactions with her, but what I do know is that both Etheleen and Lillian were fierce advocates for their children, extremely protective of their family and huge proponents of education.

Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland publicly shared her family’s personal experiences with boarding schools in a recent opinion. Haaland oversees the Bureau of Indian Education (BIE) as part of her role within the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIE). In addition to funding 135 tribally-controlled schools, the BIE currently operates 57 K-12 schools, several off-reservation boarding schools, and two universities—most of which are underfunded, understaffed and underperforming. So, while the original boarding school model no longer exists, Native American students still lack access to a quality education. There is tremendous hope that, with Sec. Haaland’s leadership, we can finally address the previously unmet needs of these schools.

As we continue to educate our peers and colleagues about the history and social inequities of Native Americans history, it’s important not to forget the scars of the boarding school era. The damage that was caused by the forced removal and separation of Native American children from their families is unspeakable: abuse, illness, and even death, all to strip young Native Americans of their cultures and languages. We’ll likely never find all the graves connected to more than 350 boarding schools across the U.S., but we can honor the survivors and all whose lives were forever changed.

Joshua Arce is the president & CEO of Partnership With Native Americans, a Native-led nonprofit organization that collaborates with reservation partners to provide consistent aid and services for Native Americans with the highest need in the U.S. Josh is a member of the Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation and has more than 20 years of experience in Native American education management, social work and business development.

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher