- Details

- By Professor Victoria Sutton

Guest Opinion. This time of year, poultry gets a lot of attention, particularly turkeys. So I’ve been thinking about how we might do better than industrial farming, which is not only cruel but also creates conditions that make an outbreak of deadly disease inevitable, as demonstrated by recent avian flu outbreaks and the massive culling of birds.

On Industrial Farming of Poultry

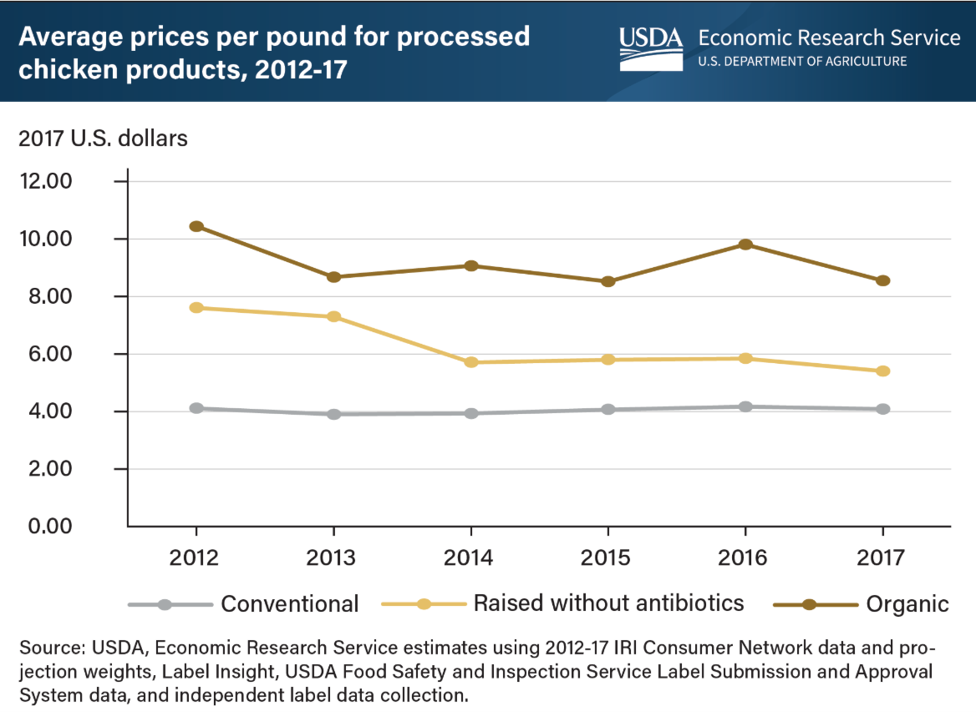

There is no question that cramped cages—often called battery cages—where a bird cannot spread its wings for its entire life, or becomes so heavy it must sit down for most of its life, are cruel. You might expect “industrialization” to provide lower costs to customers, but the price of poultry has actually risen since industrial farming began. Since 2016, USDA figures show steady increases.

Are Battery Cages for Poultry Legal in the U.S.?

At the federal level, there is no legislation prohibiting the use of battery cages. As of February 2024, the cage-free flock represented around 40% of the total egg-laying flock in the United States. In the EU, the share is about 61%, and globally around 16%. Many states, however, have passed their own laws to curtail the use of this confinement method—some within just the last few years.

State legislation in ten states since 2008 has either banned battery cages or required a 73% increase in space over the industry standard, effectively eliminating battery cages. By 2026, an estimated 16% of all layers in the U.S. will live without battery cages. The following states have passed legislation to accomplish this:

-

Arizona (sales and production bans)

-

California (sales and production bans)

-

Colorado (sales and production bans)

-

Massachusetts (sales and production bans)

-

Michigan (sales and production bans)

-

Nevada (sales and production bans)

-

Ohio (production ban)

-

Oregon (sales and production bans)

-

Rhode Island (production ban)

-

Utah (production ban)

-

Washington (sales and production bans)

Switzerland was the first country to ban cages for laying hens in 1992. The European Union banned battery cages in 2012, and several other countries, including New Zealand, have adopted similar bans.

Broiler Chickens Suffer Industrial Ambitions

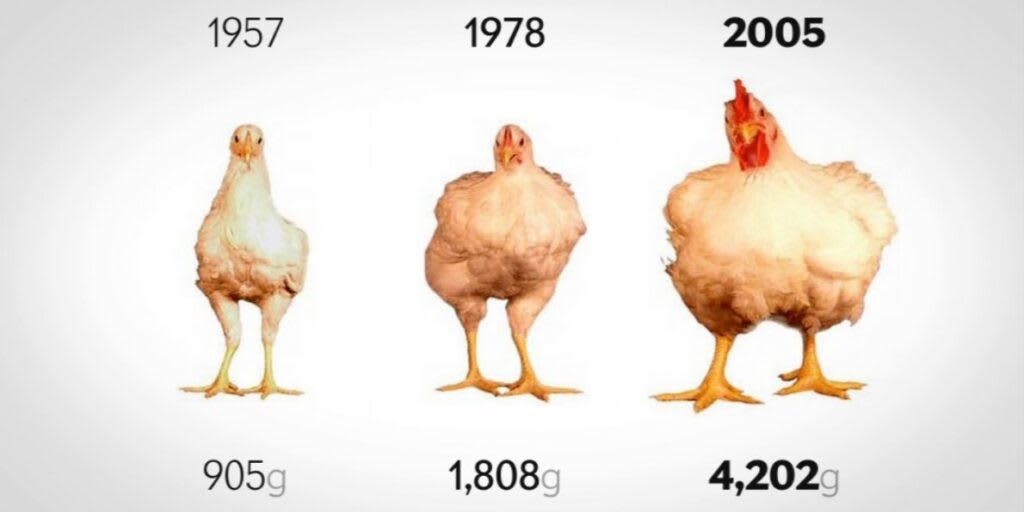

Most “broiler” chickens are selectively bred to produce the most meat in the shortest time using the least amount of feed. Modern broilers reach market weight in only six weeks. Daily growth rates have increased more than 300% in the past 50 years, from about 25 grams per day to 100 grams per day.

These broilers are selected for rapid growth and body mass. By six weeks of age, many are so large they cannot fully support their own weight, causing them to spend up to 90% of their lives lying down. Their organs often cannot sustain their size, causing pain during the final days of their lives.

The USDA issued new regulations in 2023 that establish at least some basic standards for avian species. These include requirements that surfaces be constructed of materials that can be cleaned or sanitized and that contacts with birds must be nontoxic, structurally sound, and free of sharp edges.

Organic poultry standards require more free-range activity and overall better living conditions. But as anyone who has shopped for poultry knows, organic chicken carries a premium—often 35% higher in price—while free-range chicken can be 50% higher.

Why We Should Rethink Industrialization

Prices for poultry have not dropped despite industrialization. Industrial operations are often located in low-income areas and require water-quality permits due to the massive amounts of waste they generate, putting nearby water at risk.

Disease also spreads quickly in industrial poultry operations due to the close proximity of birds. The 2014–15 avian flu outbreak in the U.S. led to 50 million birds being culled. It was less infectious for broilers but highly infectious for laying hens and turkeys, and ultimately affected poultry prices. The 2021–22 outbreak was global and began spreading to mammals such as mink and foxes.

When Animal Diseases Become a Public Health Threat

Culling diseased animals is required under federal, state, and international law. Farmers follow biosafety protocols for reporting outbreaks, collecting dead animals, testing, and culling. Culling may be ordered by state or federal authorities, and typically, when losses result from a legally defined nuisance such as disease, no compensation is paid. However, the federal government does offer compensation for farmers who follow required protocols, and some states compensate livestock owners as well.

Even so, culling must be done humanely. The Humane Methods of Slaughter Act, passed in 1958, does not include poultry, leaving “best commercial practices” as the prevailing guidance. Unfortunately, humane practices are not always followed. A recent incident in British Columbia, where more than 300 ostriches were slaughtered after an avian flu outbreak, sparked international outrage. Despite assurances that “sharpshooters” were used, many birds were found alive the next day, requiring further killing. Advocates argue the method used was among the least humane options available.

Final Thoughts

From industrial farming to inhumane culling, humane treatment of poultry is often absent. Industrialization increases the risk of disease outbreaks in tightly confined spaces, leading to mass culling orders. Even when culling is necessary, such as in cases of avian flu, it should never excuse inhumane killing methods.

Chickens and turkeys have long been important protein sources. In many Native American cultures, it is tradition to thank the animal for giving its life for food. Treating these birds humanely is a reasonable act of reciprocity.

We need to rethink how we can avoid massive kill-offs, acknowledge that industrialization has not reduced costs for consumers, and insist on humane practices for these often overlooked animals. It is time to amend statutes that currently exclude poultry from basic humane-treatment requirements.

We can do better.

To read more articles by Professor Sutton go to: https://profvictoria.substack.

Professor Victoria Sutton (Lumbee) is a law professor on the faculty of Texas Tech University. In 2005, Sutton became a founding member of the National Congress of American Indians, Policy Advisory Board to the NCAI Policy Center, positioning the Native American community to act and lead on policy issues affecting Indigenous communities in the United States.

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher