- Details

- By Levi Rickert

Opinion. In late May 2021, news broke from British Columbia of the discovery of 215 remains of innocent school children at the Kamloops Indian Residential School. The news of the mass grave caught the attention of the national and international media.

For those of us in Indian Country, the disclosure was a reminder of what most of us already knew for decades about Indian boarding schools, as they were known in the United States. We knew about the stories of the physical, emotional and sexual abuse suffered by many of the children who attended these schools. We knew that these children were beaten if they tried to speak their tribal languages. We knew that Native students died at these boarding schools.

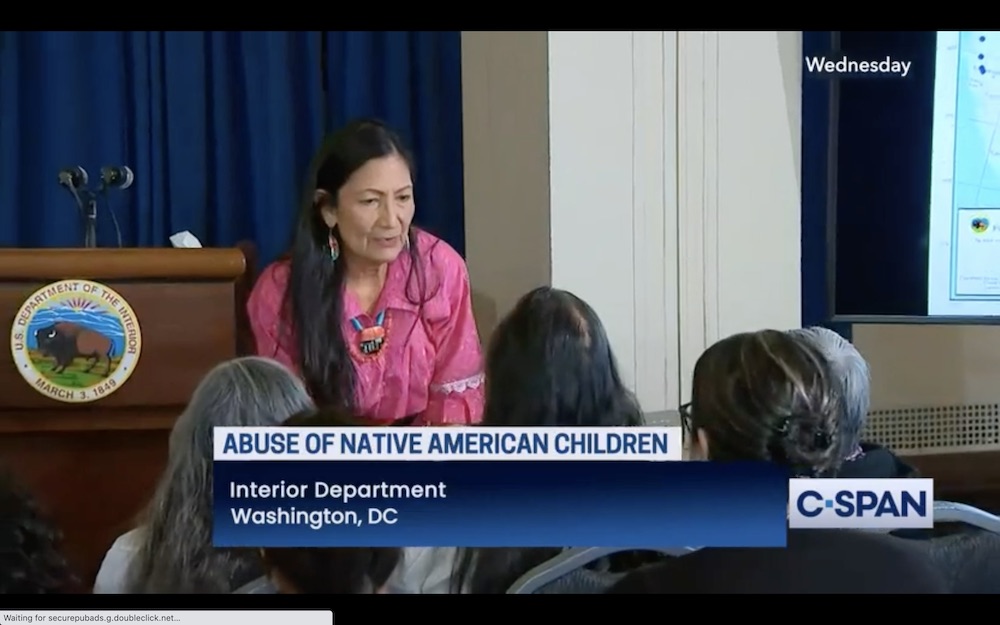

Within a few weeks, then Interior Secretary Deb Haaland (Laguna Pueblo) established the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative at the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI) 2021 mid-year conference. She charged the Initiative to uncover the full history of the U.S. Indian boarding schools program and protect sites near the schools where deceased students were buried.

Less than a year later, on May 11, 2022, the Department of the Interior released a 106-page investigative report, written by Assistant Secretary Bryan Newland that detailed for the first time that the federal government operated or supported 408 boarding schools across 37 states, including Alaska and Hawai’i, between 1819 and 1969. About half of the boarding schools were staffed or paid for by a religious institution.

When the report was released, Secretary Haaland said, “The consequences of federal Indian boarding school policies—including the intergenerational trauma caused by the family separation and cultural eradication inflicted upon generations of children as young as 4 years old—are heartbreaking and undeniable…It is my priority to not only give voice to the survivors and descendants of federal Indian boarding school policies, but also to address the lasting legacies of these policies so Indigenous peoples can continue to grow and heal.”

The report stated that the work of the Department of the Interior was not complete. Haaland then established a yearlong “Road to Healing” tour in various parts of the country. The Road to Healing tour included 12 stops where Indian boarding school survivors or their descendants provided testimony of what happened at the Indian boarding schools.

The poignant testimonies were made in tribal communities. At every Road to Healing session, Native elders testified about their memories of boarding school, including incidents of physical, emotional, and sexual abuse.

In July 2024, the Interior Department released the second investigative report that included some of those testimonies and added to previously-reported figures to paint an increasingly clearer picture of the Indian boarding school system. Between 1871 and 1969, the federal government paid more than $23.3 billion in inflation-adjusted dollars to fund the federal Indian boarding school system as well as other similar institutions.

In attendance at several of the stops was Shelly Lowe, chair of the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH). The NEH saw merit in the work of the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative, funding the documentation of the testimonies heard during the Road to Healing and stories collected from other Indian boarding school survivors. She resigned as chair of the NEH last month at the request of President Trump.

Last week, the Washington Post reported the Trump administration pulled the $1.5 million funding that was earmarked for 10 organizations that would preserve Indian boarding school documents by digitizing them.

One of those organizations is the Minneapolis-based National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition (NABS), which lost $282,000 in NEH funding. Deb Parker, CEO of the coalition told Native News Online on Saturday that if this work cannot continue, future generations — both Native and non-Native — will have limited access to the truth about the boarding school era.

“This loss not only hinders education, but also deepens the gap in our national understanding, allowing cycles of erasure, misunderstanding, and invisibility to persist,” Parker said. “Finding and preserving government and church records pertaining to what happened to Native American children in Federal Indian Boarding Schools is not just an act of remembrance—it’s a commitment to future generations, and a necessary step toward truth and healing in this country.”

The NEH funding supported projects that gave voice to survivors and descendants who have waited far too long to be heard. These projects are acts of truth-telling and healing. Now, they are being abandoned.

Let’s be clear: this is not just a bureaucratic budget cut. This is an erasure—a willful, dangerous denial of a painful and still-present chapter of American history.

Another word for erasure is sanitize. It is not proper to attempt to sanitize history.

Thayék gde nwéndëmen - We are all related.

More Stories Like This

Tribal Economic Development Programs in the Federal Contracting Environment: What They Are, and What They Are NotWhy Redefining Public Health Degrees Would Harm Native and Rural Communities

The SAVE America Act Threatens Native Voting Rights — We Must Fight Back

The Presidential Election of 1789

Cherokee Nation: Telling the Full Story During Black History Month

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher