- Details

- By Professor Victoria Sutton

Guest Opinion. Water makes up about 60 percent of a human body (varies by age) and up to 90 percent of some living organisms. The conventional wisdom still holds that you should drink eight, 8-ounce glasses of water a day, but this can come from fruits and other foods with high water content.

Where is the water?

Water on Earth covers about 71 percent of the planet’s surface, so you would think we might have more than enough water for humans. But freshwater, the amount that is usable by humans is only about 3 percent of it. The freshwater is not all that easy to use. One-third of it is in groundwater, recharged by rain and snow seeping into the underground crevices; two percent is rivers, lakes and streams; and there is a small amount in the atmosphere in the form of clouds. The majority of freshwater is glaciers and ice, mainly in the polar regions of the Earth. There are two billion people or 26 percent of the world’s population, who lack access to safe drinking water.

Indigenous Worldviews of Water

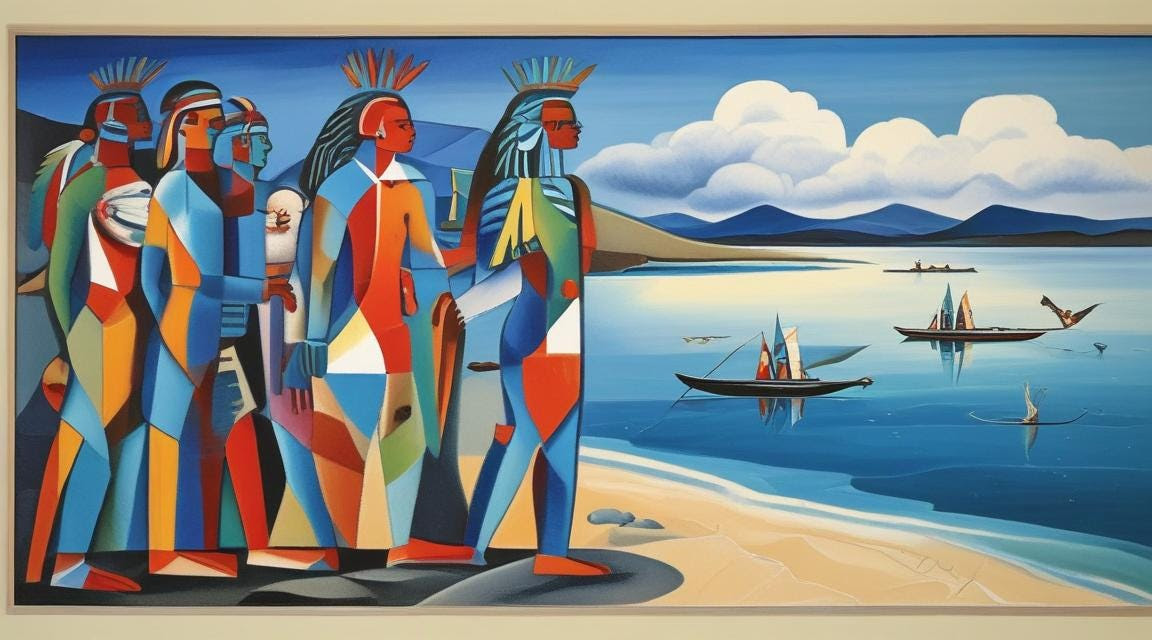

Water is the lifeblood of the Earth. It has its own spirit and it is a relative. Water has a life and deserves respect. Many tribes take their name from the River from which they rely for food and water. Water protectors are usually women who have responsibility for ensuring that the water is respected and protected. Women are usually the water protectors because water is associated with childbirth and the beginning of life. Keepers of the River, or River Keepers are also roles that involve protection of a particular river that is considered sacred by a tribal culture.

Some (both Native and Non-Native) believe that water has legal rights such as the right to exist and the right to not be polluted. Native Nations have increasingly passed tribal laws that give rights to bodies of water. One of the first Nations to recognize these legal rights is New Zealand when the country recognized the Wanganui River as a “person” under the law, bestowing rights for its protection.

Water for Native Americans

In July 2024, Navajo Nation President Buu Nygren testified in the U.S. Congress that legislation to bring water to the Navajo Nation was critically needed. It is a hearing that everyone in America should know had to take place because two of the three branches of government have turned their back on the fair and legal distribution of water to the Navajo Nation. The executive branch, the President signed a treaty with the Navajo Nation that should have made water available to them for survival and growing food at a minimum. Instead, the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) and U.S. Department of the Interior have allowed the surrounding states and private landowners to illegally take use of the water in violation of the treaty as well as the Winters Doctrine. The U.S. Supreme Court was asked last term, simply to define what rights they had in their treaty, and they declined to do so, in an odd action on the part of the court, after they accepted the case to hear the legal issues. Instead, they made up their own questions and answered those — they opined that the United States may have guaranteed water but they didn’t guarantee that they would deliver it. Now, the Navajo Nation is asking the third and last branch of the U.S. Government — the U.S. Congress — to remedy this human rights violation.

It is not just the Navajo Nation with this inequity with water. In 2021, a U.S. House Committee report found that on all reservations, 48 percent of households lack adequate water. About a century earlier, the Merriam Report found that adequate water was not available to reservation homes. The problem is not new and it is knowingly being ignored by our collective government.

The Black Snake and the Water Protectors

The sacred Lake Oahe on the Standing Rock Sioux reservation lands was the selected pathway for the Dakota Access Pipeline (although there were better routes, but through more politically powerful non-Indian lands). In July 2016, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers approved the permit to bury this pipeline through the lake that was the source of freshwater for the reservation. Despite promises that it would not leak, the reported leaks from pipelines numbered in the hundreds according to the agency that tracks this data, the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration. The Environmental Impact Statement had found that going through the reservation water resource avoided “sensitive” water resources, which presumably meant those in cities outside of the reservation. By December 2016, after protests drew protestors from around the world, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers withheld a key final permit and stopped the project. The incoming Trump Administration reversed this decision and accelerated the process to proceed with the pipeline. The pipeline was built, and the Biden Administration made a decision to keep it open.

Only when the last tree has died and the last river has been poisoned and the last fish has been caught will you realize you cannot eat money.

—- Cree Nation

Water protectors received global notoriety during the Dakota Access Pipeline protests as they were on the front lines of the resistance; but they have been a part of Indigenous culture since the beginning of time. Water Protectors may be selected at birth or very early in life, and live their life in getting to know and understand the water, river or lake that is closely associated with them. That can be understanding the cycles of the river, learning from the river when the river reveals important lessons about it and its inhabitants.

What must be done

The lack of adequate water due to duplicity and outright deceit in treaties that impliedly include adequate water (That is the Winters Doctrine.) is but one factor in this widespread lack of access to water. Disproportionate mining and drilling activity on reservation lands pollutes freshwater resources through runoff, and dumping. A third disproportionate activity in areas where Native people live is the permitting of various industrial processes, like mining and drilling, even industrialized farming where drinking water or surface water is taken and used as part of the industrial process.

These three pressures on water for reservation homes, must all be addressed to resolve the problem. To do that we all must share the mission of the Water Protectors.

To read more articles by Professor Sutton go to: https://profvictoria.substack.

Professor Victoria Sutton (Lumbee) is a law professor on the faculty of Texas Tech University. In 2005, Sutton became a founding member of the National Congress of American Indians, Policy Advisory Board to the NCAI Policy Center, positioning the Native American community to act and lead on policy issues affecting Indigenous communities in the United States.

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher