- Details

- By Jeremy Harley

Guest Opinion. Thanksgiving has always been a conflicting time for me as an Indigenous person. In elementary school, I remember being forced to craft a paper pilgrim hat, as I had to watch another class of non-Indigenous people appropriate my culture as they created feathered headbands and painted their faces. We reenacted scenes of a peaceful feast shared between the Native Americans and Pilgrims. Teachers spoke of gratitude and cooperation, but no one ever asked me, the lone Native student in my class, how I felt about it. No one mentioned the pain, loss, or survival of my ancestors.

To everyone else, it was just a holiday. To me, it was a reminder of a story that had been rewritten to exclude the voices of my people.

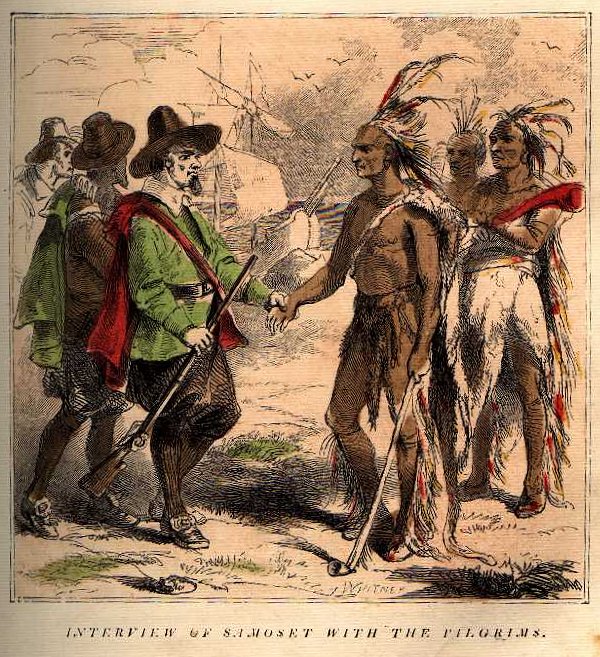

The Thanksgiving myth, as told in schools, paints an idyllic picture of unity and gratitude. We are taught that Pilgrims and Native Americans shared a meal, fostering peace and mutual respect, but the true history tells a far different story.

The "first Thanksgiving" in 1621 was a shared meal between the Wampanoag people and the Pilgrims, but it wasn’t a celebration of harmony, but rather a momentary truce. The Wampanoag, led by Massasoit, had just survived a devastating plague brought by European settlers, which decimated their population. However, they noticed the Pilgrims were struggling to survive with their limited knowledge of how to hunt, farm, and navigate this new land.

The Wampanoag people would aid these settlers in their time of need and teach them the proper techniques on how to live off the land. What followed in the decades after was not partnership, but betrayal. Native lands were seized, treaties were broken, and violence escalated. Incidents such as The Pequot Massacre of 1637, are often overlooked, but ended with hundreds of Native men, women, and children killed.

These incidents were not just isolated events. The forceful taking of lands, breaking of treaties, and the passing of discriminatory legislation were all practices occurring up and down the East Coast. My tribe, Piscataway Conoy, first interacted with the English settlers during the infamous Starving Times of the early Jamestown settlement.

The Piscataway aided the settlers to defeat the food embargo placed on them by the Powhatan people. Following the embargo, the settlers and my people engaged in mutually beneficial trade. We would get various European goods such as blankets, iron axes, steel knives, and more in exchange primarily for food, and eventually fur, during the high times of the fur trade.

The settlers engaged in this trade because they needed our people's involvement to sustain their settlements and fuel their economies. However, once the services of our people were no longer needed, we were only in their way. We were occupying land they decided was theirs.

It wasn’t very long until colonial governments executed forced removals of our people and relocated them further west. After decades of violent hostilities and land disputes, the 1677 Treaty of Middle Plantation proposed a deal to solve all issues. We were guaranteed control over our traditional homelands, hunting and fishing rights, and other rights if we maintained English loyalty. As time passed and the Colonist's lust for land grew, our rights guaranteed in this treaty soon became ignored. We were no longer partners pursuing a mutual benefit, but now only mere subjects of the English crown.

While Thanksgiving has evolved into a symbol of gratitude and family, its historical roots are in colonization, exploitation, and the systematic erasure of Indigenous peoples. Even beyond the holiday itself, the legacy of this erasure persists. The United States was built on stolen land, and the displacement of Native peoples has been followed by attempts to strip us of our culture, language, and identity. Boarding schools, forced assimilation, and discriminatory policies have left scars that many of our communities still carry today.

Thanksgiving can no longer be a comfortable celebration of myths. It should be a time to reflect on the real history of this land, to honor the resilience of Native peoples, and to recognize the injustices that continue to affect us.

Despite all this, Thanksgiving is a holiday my family and I still celebrate. Instead of abandoning already existing traditions, I invite you to expand your understanding and learn about the history of the Wampanoag people and their descendants, and the tribes that are local to your area. Try to understand the impact of colonization and listen to the stories of Native communities who fight to preserve their culture and sovereignty.

We cannot change the past, but we can honor it by seeking the truth and committing to a better future. This Thanksgiving, as you gather with your loved ones, take a moment to reflect on the land you stand on and the people who were here before you. Let’s move forward together, not by clinging to myths, but by acknowledging the full story of our shared history.

Jeremy Harley is a citizen of the Piscataway Conoy Tribe, a state recognized tribe in Maryland, and one of the traditional historic tribes of the East Coast. Harley is a 2023 University of Maryland graduate.

Help us ensure that the celebration of Native Heritage never stops by donating here.

Help us tell the stories that could save Native languages and food traditions

At a critical moment for Indian Country, Native News Online is embarking on our most ambitious reporting project yet: "Cultivating Culture," a three-year investigation into two forces shaping Native community survival—food sovereignty and language revitalization.

The devastating impact of COVID-19 accelerated the loss of Native elders and with them, irreplaceable cultural knowledge. Yet across tribal communities, innovative leaders are fighting back, reclaiming traditional food systems and breathing new life into Native languages. These aren't just cultural preservation efforts—they're powerful pathways to community health, healing, and resilience.

Our dedicated reporting team will spend three years documenting these stories through on-the-ground reporting in 18 tribal communities, producing over 200 in-depth stories, 18 podcast episodes, and multimedia content that amplifies Indigenous voices. We'll show policymakers, funders, and allies how cultural restoration directly impacts physical and mental wellness while celebrating successful models of sovereignty and self-determination.

This isn't corporate media parachuting into Indian Country for a quick story. This is sustained, relationship-based journalism by Native reporters who understand these communities. It's "Warrior Journalism"—fearless reporting that serves the 5.5 million readers who depend on us for news that mainstream media often ignores.

We need your help right now. While we've secured partial funding, we're still $450,000 short of our three-year budget. Our immediate goal is $25,000 this month to keep this critical work moving forward—funding reporter salaries, travel to remote communities, photography, and the deep reporting these stories deserve.

Every dollar directly supports Indigenous journalists telling Indigenous stories. Whether it's $5 or $50, your contribution ensures these vital narratives of resilience, innovation, and hope don't disappear into silence.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Native languages are being lost at an alarming rate. Food insecurity plagues many tribal communities. But solutions are emerging, and these stories need to be told.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Native languages are being lost at an alarming rate. Food insecurity plagues many tribal communities. But solutions are emerging, and these stories need to be told.

Support independent Native journalism. Fund the stories that matter.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher