- Details

- By Darren Thompson

The Fort Belknap Indian Community is suing the federal government for not providing adequate law enforcement services on Indian lands.

According to court documents, the Tribe filed a lawsuit last October after it was denied a $3.8 million increase for law enforcement funding from the previous year.

In its filing, lawyers for the Tribe wrote, “The population of the Reservation is substantially harmed by violent crime, crimes against children and vulnerable adults, missing persons, drug-related crime, and the resulting impacts to the entire Reservation community.”

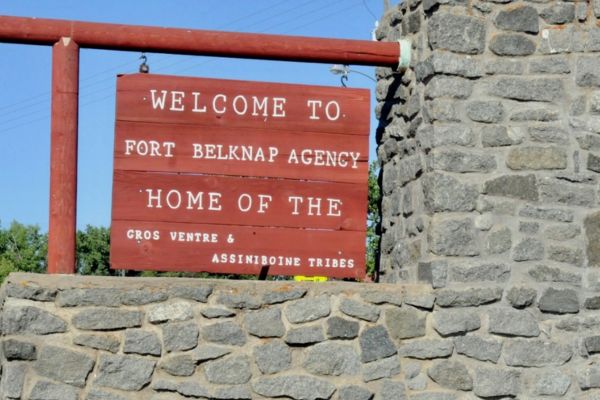

The Fort Belknap Indian Reservation is homeland to the Gros Ventre and the Assiniboine tribes, both of which comprise the government of Fort Belknap Indian Community. The Tribe’s reservation is approximately 637,000 acres and has approximately 3,182 people living within its boundaries that receive tribal law enforcement services.

The Tribe’s members are dependent on federally funded law enforcement officers to protect them and their on-reservation property.

“Tribe’s current number of law enforcement officers and criminal investigators is insufficient to fulfill the Defendants’ obligations to keep the peace on the Fort Belknap Indian Reservation,” said the Tribe’s attorneys in its filing on October 22, 2022.

The Tribe reported that its Chief of Police is paid 50% of a Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) Chief of Police salary, six of its seven Tribal police officers are paid at 70% of a BIA police officer’s salary and its sole criminal investigator makes approximately 50% of a similar BIA employee’s salary. The Tribe's four dispatchers are paid at approximately 50% of a similar BIA dispatcher and its secretary is paid at 70% of a BIA secretary.

In addition, with the proposed increase in funding the Tribe is hoping to provide additional law enforcement services such as a victim outreach coordinator, more criminal investigators including a drug investigator, program specialist, K-9 officer and drug dog, school resource officer, and a Missing and Murdered Indigenous Persons Special Agent.

The Tribe states that in its review of Annual Funding Agreements (AFA) that the defendants, including the United States, the U.S. Department of Interior, the Secretary of Interior, the Assistant Secretary of Interior, and other BIA staff have been underfunding Tribal law enforcement since 2015.

According to court documents, Tribal law enforcement has been underfunded from 2015 to 2022 by approximately 50% for salaries and 75% for operational costs.

After the Tribe submitted its AFA request on July 1, 2022, the BIA-Office of Justice Services (OJS) sent a letter to the Tribe on August 24, 2022 denying their request of $5.3 million and requested that Tribe resubmit its proposed AFA without the increased budget amount. On September 26, 2022, the BIA Office of Justice Services issued a letter to the Tribe, partially declining the proposed 2022-2023 AFA for all funding above $1,353,247.

The Tribe says that the funding leaves them without adequate law enforcement services on the reservation. All funds held by the United States for Indian Tribes, or federally recognized Tribes, are held in trust. A trustee, the United States, is accountable in damages for breaches of trust.

It's asking for a permanent injunction that upholds the defendants from distributing law enforcement funding at levels below what is required to fulfill Treaty, statutory, and fiduciary obligations to the Tribe based on the reservation’s population of 3,182 people.

Last July, the Northern Cheyenne Tribe in Montana filed a lawsuit against the BIA and the Department of Interior, saying that the U.S. federal government is failing to meet its treaty obligations to provide adequate law enforcement services to the reservation.

Both Fort Belknap and Northern Cheyenne join the Oglala Sioux Tribe and the Rosebud Sioux Tribe in separate lawsuits alleging that the federal government is failing to keep Tribal communities safe.

On Monday, Native America Calling hosted leaders from the Fort Belknap Indian Community and the Northern Cheyenne Tribe in a discussion that focused on how lack of funding for law enforcement on Indian reservations leads to increased crimes and victims.

Jeffrey Stiffarm, President of the Fort Belknap Indian Community, shared on the program that in the fall of 1997, the Tribe voted to provide its own law enforcement on the reservation rather than the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Stiffarm said that the contract negotiated with the BIA-OJS was for 10 tribal police officers at $10 per hour equivalent to $1.2 million per year.

A police veteran in the community, he said that in the six years he’s been involved in Tribal politics, he has traveled to Washington, D.C. several times to lobby for increased funding for law enforcement.

“What is really frustrating with me is you see other BIA-run departments, that are not run by Tribes, and their base funding is two or three times the amount that they give to Tribes,” Stiffarm said on Native America Calling. “Their response is always that they have no more money to give Tribes.”

Sometimes, there is only one police officer covering more than 1,000 square miles. “This isn’t just a community issue, it’s an officer safety issue,” Stiffarm said. “The community knows when there is only one person on staff.”

More Stories Like This

50 Years of Self-Determination: How a Landmark Act Empowered Tribal Sovereignty and Transformed Federal-Tribal RelationsThe Shinnecock Nation Fights State of New York Over Signs and Sovereignty

Navajo Nation Council Members Attend 2025 Diné Action Plan Winter Gathering

Ute Tribe Files Federal Lawsuit Challenging Colorado Parks legislation

NCAI Resolution Condemns “Alligator Alcatraz”

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher