- Details

- By Jenna Kunze

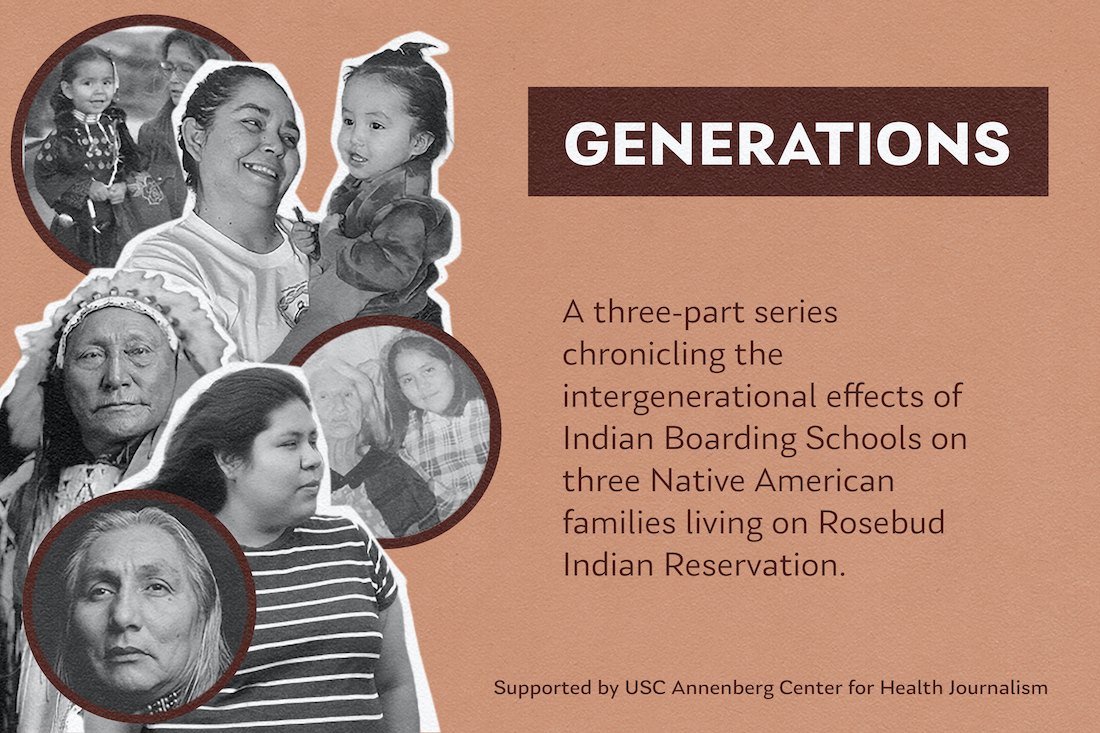

A special three-part series following the intergenerational effects that the United States government’s century-and-a-half practice of placing Indian children in boarding schools has had on three families living on Rosebud Indian Reservation in South Dakota. This story was produced as a project for the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism's 2021 Data Fellowship.

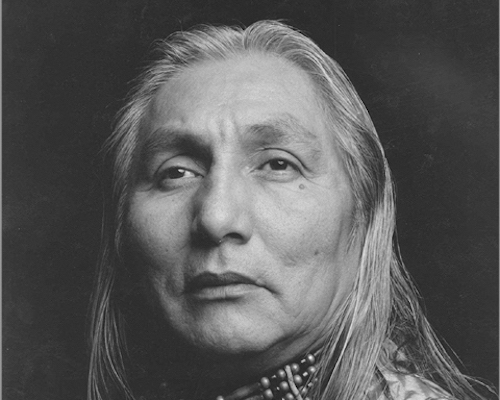

Part One: Survivors

Now in his 70s, Duane Hollow Horn Bear was part of the last generation to attend an institution designed by the U.S. government to strip Natives of their culture and lands, but he’s not the last or the only one to live with the effects caused by Indian boarding schools.

He entered St. Francis Mission school when he was eight years old and stayed until he graduated, at 20. The old school buildings have since been demolished and rebuilt. But the memories remain.

Perhaps the largest scar that boarding school left on Hollow Horn Bear and the preceding generations came from its separating Native kids from their families, languages, cultures, and traditions for nine months of each year of their entire adolescence. Growing up mostly without his parents and grandparents, he said he didn’t know how to raise children, and eventually neglected his own.

Read the story.

Part Two: First Generation Descendants

Part Two: First Generation Descendants

In scrolling black ink, LeToy “Toy” Lunderman illustrates intergenerational trauma like this: three big circles represent three generations, the first circle nearly empty but for a sliver of solid—representing all that was taken from survivors of boarding school—and the subsequent circles gradually filling with solid until the last circle is whole again.

She’s the middle circle, the conduit between hardship and healing, among the generation of children born in the mid ‘70s who grew up in the years immediately after the federal government abandoned its Indian Boarding School policy.

But it would take her a while to recognize how deeply she’s been impacted by a school system she didn’t directly experience, though she was educated in the same buildings where many in the generations before her experienced abuse: Saint Francis Indian School, formerly Saint Francis Mission, on the Rosebud Indian Reservation in South Dakota.

Read the story.

Part Three: Young Adults Today

Part Three: Young Adults Today

They were just kids when they learned about the Native children, their ancestors, who never came home from Indian boarding school more than a 100 years before.

Seven years ago, a group of Rosebud Sicangu Youth Council members were traveling back from a conference in Washington when the tribal leaders chaperoning them suggested that the group make a side trip to see a bit of their history: the site of the former Carlisle Indian Industrial School, in Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

Now, young adults on the Rosebud Indian Reservation continue to lead the efforts to bring home lost ancestors buried at the former boarding schools—all while coming to terms with the ways in which their grandparents’ and great-grandparents’ experiences at those schools affect their lives today.

Read the Story.

More Stories Like This

Committee Advances 20% Increase to Navajo Child Support GuidelinesNavajo Committee Advances $84M Transportation Improvement Plan

NCAI Passes Two Emergency Resolutions on Immigration Enforcement Activities

Chickasaw Lighthorse Police Officer named Indian Country Law Enforcement Officer of the Year

Indian Gaming Association Rallies Broad Coalition Against Sports Event Contracts It Calls Illegal Threat to Tribal Sovereignty

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher