- Details

- By Tanya Gibbs, Rosette, LLP

The low-income housing tax credit program (LIHTC Program) was created by the Tax Reform Act of 1986.1 Although it is a federal program, it is administered by states and is available to real estate owners and private developers, including tribes and tribally owned entities. However, the LIHTC Program is not always easily accessible to tribes. Since its inception, the LIHTC Program has allowed for the creation of over 3.2 million housing units nationwide,2 of which just over 31,000 were within Indian Country as of 2019 (just .9%).3

Each state agency that administers the LIHTC program does so through a very competitive process outlined in an annual qualified allocation plan (QAP). Unfortunately, many (if not most) QAPs heavily favor populated urban areas rather than rural areas even where there is a demonstrated need for housing units. This favoring of urban areas to the disadvantage of rural areas disproportionately affects tribes because their reservations are often located far from urban centers. For example, in 2021, of the 25 projects Michigan awarded,4 only one is located on tribal lands.5 Michigan is one of a handful of states that have implemented some kind of tribal “set-aside” in their QAP to guarantee access to projects for tribes. While this ensures at least one tribal project will get picked each year, it can also create fierce competition among the tribes or result in the same tribes (because they are more urban or have more experience) getting picked year after year. Rural tribes then continue to be left out facing severe affordable housing shortages.

One thing is certain: tribes must start taking advantage of the LIHTC Program. One approach might be to use the LIHTC Program as part of a tribe’s overall economic development strategy. LIHTC awards are not limited to tribal government housing departments and programs but can also be used by tribal economic development companies (EDCs).

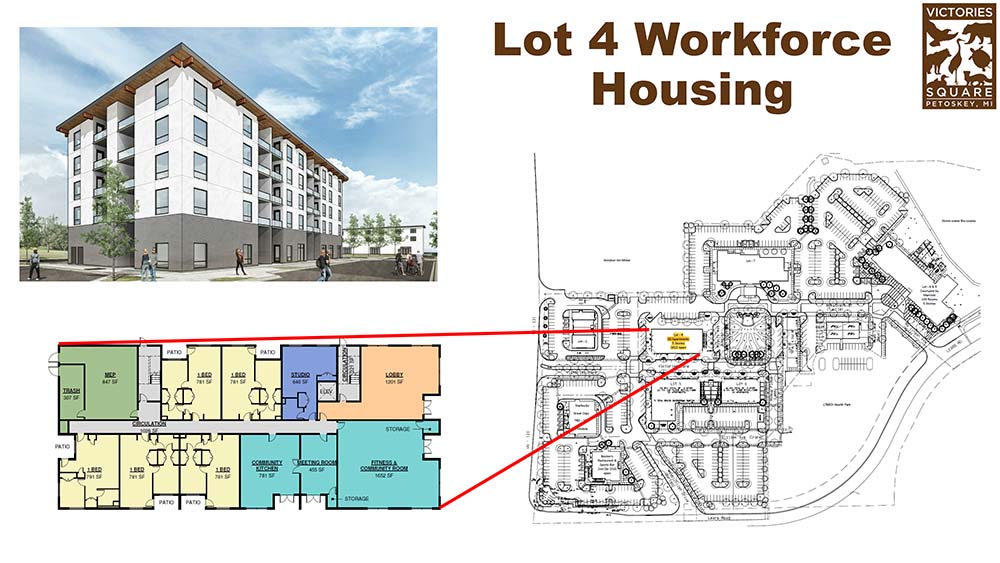

Tribal EDCs are massive economic drivers in their respective states,6 but unfortunately states do not always realize the economic impact that tribal EDCs have on the state economy. As on-reservation economic development grows, so does the need for a substantial workforce to staff tribal enterprises. Those tribal employees need an affordable, comfortable place to live with their families. Using LIHTC to create work force housing is a great way for tribes to continue to be the economic drivers in their local communities as well as help those communities meet an unfulfilled need.

In order to do so, it is important for tribes to educate their state counterparts and specifically, state housing agencies to ensure tribal LIHTC projects have a fair chance at receiving awards. Tribal EDC board members and executive leadership, along with elected tribal leadership, need to drive the conversation with the states. In these conversations, tribal stakeholders should push for fair treatment and inclusion, identify areas where a state’s QAP disadvantages tribes and rural communities, and offer alternative solutions that actually make sense. It may also be important to share the overarching goals of the tribal EDC and explain how LIHTC can be a key component of further economic diversification, as this is often something that state stakeholders do not understand.

The time to have these conversations is now. Current federal policy is favorable for tribes engaging in economic development and consultation with states. Further, the Build Back Better Act that is currently being considered by the Senate includes a 10% increase in LIHTC Program funding, with an annual inflation adjustment for future sustainability of the program.7 The legislation also addresses the lack of incentives state agencies face by establishing a 50% basis boost for extreme low-income housing8 and a 30% basis boost for properties in tribal areas. The goal is to incentivize investment in tribal housing by making those investments more lucrative and combat the inherent bias in the state-centric regulatory regime of the LIHTC Program. Tribes should therefore consider supporting favorable federal policy, continuing conversations with state housing agencies, and working to implement LIHTC programs that help further their economic growth and diversification.

- 26 U.S.C. § 1 et seq.

- HUD User Office of Policy Dev. And Research, Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC): Property Level Date, https://www.huduser.gov/portal/datasets/lihtc/property.html#query

- Evelyn Immonen and Keith Wiley, Low Income Housing Tax Credits in Indian Country, Housing Assistance Council, https://www.ncai.org/policy-research-center/initiatives/LIHTC_in_Indian_Country.pdf

- https://www.michigan.gov/mshda/about/press-releases/2021/07/15/mshda-awards-27-9-million-in-tax-credits-for-affordable-housing-development-projects-across-michiga; Rachel Watson, MSHDA awards $27.9M in tax credits for affordable housing development projects, Grand Rapids Business Journal, https://grbj.com/news/government/mshda-awards-27-9m-in-tax-credits-for-affordable-housing-development-projects/

- Id.

- Native News Online, STUDY: Non-Gaming Tribal Businesses in Michigan Generate $288.8M Economic Impact, https://nativenewsonline.net/business/study-non-gaming-tribal-businesses-in-michigan-generate-288-8m-economic-impact#:~:text=Tribal%20gaming%20facilities%20in%20Michigan,to%20the%20American%20Gaming%20Association; Eric S. Trevan and John Deacon Panamaroff, Michigan Non-Gaming Tribal Economic Impact Study, Wasayabek Development Corp., https://wdcmultisite.com/wdc/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2020/07/Michigan-Non-Gaming-Tribal-Econ-Impact-Study-2019-Summary-Booklet-FINAL-AND-APPROVED-3.pdf

- Build Back Better Act, H.R. 5376, 117th Cong. § 135302, 135101(a)(I)(ii) (Nov. 2021).

- Id. at § 135103(b).

Help us tell the stories that could save Native languages and food traditions

At a critical moment for Indian Country, Native News Online is embarking on our most ambitious reporting project yet: "Cultivating Culture," a three-year investigation into two forces shaping Native community survival—food sovereignty and language revitalization.

The devastating impact of COVID-19 accelerated the loss of Native elders and with them, irreplaceable cultural knowledge. Yet across tribal communities, innovative leaders are fighting back, reclaiming traditional food systems and breathing new life into Native languages. These aren't just cultural preservation efforts—they're powerful pathways to community health, healing, and resilience.

Our dedicated reporting team will spend three years documenting these stories through on-the-ground reporting in 18 tribal communities, producing over 200 in-depth stories, 18 podcast episodes, and multimedia content that amplifies Indigenous voices. We'll show policymakers, funders, and allies how cultural restoration directly impacts physical and mental wellness while celebrating successful models of sovereignty and self-determination.

This isn't corporate media parachuting into Indian Country for a quick story. This is sustained, relationship-based journalism by Native reporters who understand these communities. It's "Warrior Journalism"—fearless reporting that serves the 5.5 million readers who depend on us for news that mainstream media often ignores.

We need your help right now. While we've secured partial funding, we're still $450,000 short of our three-year budget. Our immediate goal is $25,000 this month to keep this critical work moving forward—funding reporter salaries, travel to remote communities, photography, and the deep reporting these stories deserve.

Every dollar directly supports Indigenous journalists telling Indigenous stories. Whether it's $5 or $50, your contribution ensures these vital narratives of resilience, innovation, and hope don't disappear into silence.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Native languages are being lost at an alarming rate. Food insecurity plagues many tribal communities. But solutions are emerging, and these stories need to be told.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Native languages are being lost at an alarming rate. Food insecurity plagues many tribal communities. But solutions are emerging, and these stories need to be told.

Support independent Native journalism. Fund the stories that matter.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher