- Details

- By Jenna Kunze

THOROUGHFARE, Virg. — Last week, Prince William County supervisors in northern Virginia voiced support for the relatives of about 100 freed slaves and Native Americans whose gravesites were disturbed in a private property owner’s land clearing.

“It angered me and it broke my heart to see what happened there,” Supervisor Pete Candland, R-Gainesville, said at the May 4 board meeting. “Part of the accountability is understanding how the county fell short and how we can address it.”

The town of Thoroughfare sits 40 miles east of Washington D.C. Due to a long history of settlement, there are three historic cemeteries in the area—one of which falls in the far corner of land near a brewery.

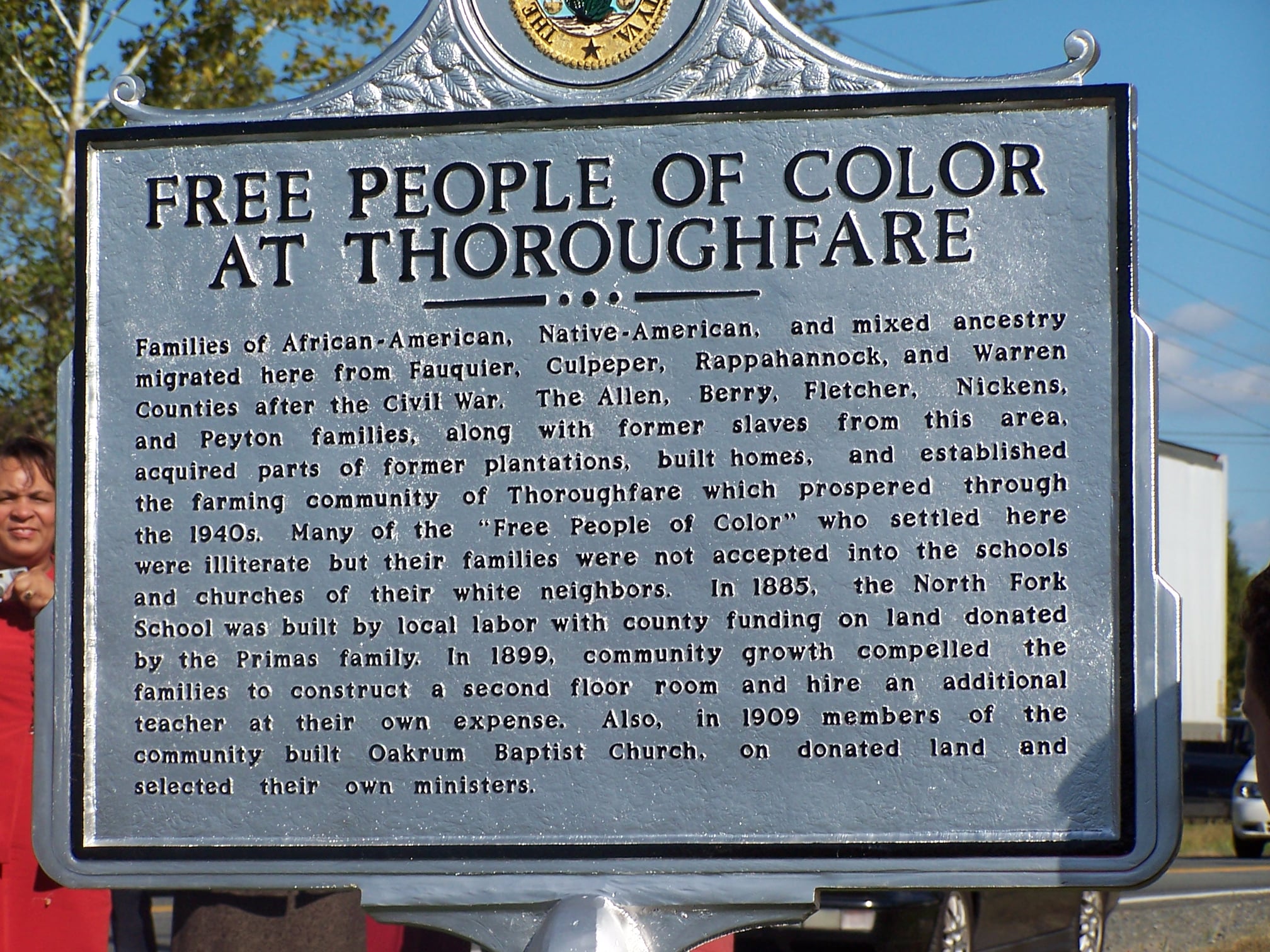

A plaque along Route 55 near Thoroughfare marking the historic district explains that families of African-American, Native American, and mixed-ancestry settled there after the civil war to establish farming communities on former plantations.

A plaque along Route 55 near Thoroughfare marking the historic district explains that families of African-American, Native American, and mixed-ancestry settled there after the civil war to establish farming communities on former plantations.

The co-owner of the company that owns the parcel, Bill DeWitt— whose wife owns the brewery—said that last month, he cleared two and a half acres of forested land to plant crops of corn and sunflowers. DeWitt, who had no knowledge of the historic Scott Cemetery on the property at the time, asserted that no excavation took place. He said he used a skid steer forestry attachment to move 60 tons of debris off the property, but that he didn’t see any rocks that could have been headstones. “All we did is we cut down trees and pulled out stumps,” he said. “We didn’t excavate to the point where we would exume or knock down headstones.”

When Justin Patton, the county’s lone archaeologist, heard reports of clearing on the DeWitt’s property, he made a site visit, then put in a call to police to notify them of a non-permitted land clearing on what he knew to be a historic cemetery.

Despite a nonexistent record of the historic cemetery in real estate assessments and deeds to the property, Patton had knowledge of the burial site from a walking survey he did in 2007, though he didn’t take photos or field notes at the time. He said he visually noted between 75 and 100 gravesites marked by common field stones and slight depressions in the earth. The archeologist said that, because the county didn’t have a stone cutter to make formally inscribed headstones until around 1825, most gravesites were marked by field stones. “Most people walking through the woods… would be unlikely to recognize that as a burial,” Patton said. “They're not trained to look at it that way.”

DeWitt, who said he believed he was acting within the code by removing debris from his land for agricultural purposes, stopped operations when the county issued him a violation for clearing without a land disturbance permit. At the time it was issued, Patton said, the office didn't know that there was a cemetery on the property. DeWitt told Native News Online that he “stopped everything” before any plows were run.

Part of the challenge, according to county public works director Tom Smith, is that none of the historic cemeteries exist on property records.

But Patton, who was called on by the Commonwealth attorney and police investigating the case to submit observations, said that the ground surface where the DeWitts cleared dead underbrush and trees, in his opinion, is not the original surface that existed before clearing took place.

“If there are headstones there that exist now, they are covered up,” he said. “If they have been moved, because the ground surface is not in its original state, I can't tell that unless we do some archaeology.”

Prince William County Police Department conducted an investigation last month, and referred its findings to the Office of the Commonwealth’s Attorney, the department said in an email to Native News Online.

Displacing human remains is a Class 4 felony under Virginia law, though in order to prosecute an attorney must be able to prove “willful or malicious damage.”

According to the Office of the Commonwealth’s Attorney, the investigation concluded that no criminal intent was involved, so the Commonwealth won’t seek criminal charges in the matter.

“Our office has been made aware of the investigation by the Prince William County Police Department,” the Commonwealth’s Attorney office said in a statement to Native News Online.

“There is nothing in the report received by our office from the Police Department to indicate any willful intent on the part of the property owner to desecrate gravesites. Given that no criminal charges have been filed with our office, litigation related to this incident will likely be civil and/or zoning related in nature.”

***

Despite an apparently closed case, one descendant of Thoroughfare whose lineage dates back to 1855, Frank Washington, has made it his mission to seek justice for the disturbed gravesites, and protect the remaining sites from future development.

Thoroughfare’s two other historic gravesites include the Peyton Cemetery, a community cemetery adjacent to the brewery holding about 80 to 100 gravesites, and the still active Fletcher-Allen graveyard located on the other side of a grove of trees from the Peyton Cemetery, which hold the remains of Washington’s grandparents, aunts and uncles, cousins and great grandparents.

“I feel hurt by what's going on,” Washington told Native News Online. “I feel like the respect that they didn't get in life, they're not even getting in death, which really bothers me.”

Washington has spearheaded a group, Coalition to Save Historic Thoroughfare, to hold press conferences and gain support, including through awareness brought by media attention.

Because the Peyton Cemetary is on unplatted land, and many gravesites are not obviously marked, Washington worries that a threat of future development could disturb some of the graves. Between the three burial grounds, he estimates there are more than 250 graves.

Washington has enlisted the help of Patton to document the Peyton and Fletcher-Allen cemeteries. Last month, the descendant noticed surveyor’s flags around a group of gravesites in the Peyton Cemetery, bringing to life the threat of pending residential development.

“It's all been happening so quickly,” Washington said. He said he was told by surveyors that the boundaries were set, and that no more burials could be added to his family’s cemetery.

“Which goes against our oral history, because most of my relatives, including myself, were told all of our lives that we'd have a resting place beside our loved ones ancestors if we chose,” he said. “If what happens now goes through the way it is, that will no longer be the case.”

Supporters offer prayers and healing

Two weeks ago, the Coalition to Save Historic Thoroughfare held a cleansing and healing ceremony for the disturbed gravesites at the Oakrum Baptist Church in Thoroughfare. More than 100 people came to show their support, Washington said.

Sheila Hansen, a Shawnee descendant and founder of an organization United Tribes of the Shenandoah for other Virginia Native Americans that were never able to gain tribal citizenship, said the ceremony consisted of smudging, a drum and prayer circle, and speeches from allies visiting from Lakota tribes, a nearby Buddhist temple, and Washington D.C.

“At the beginning of that part of that ceremony, two eagles made a circle around us,” Hansen said. “We knew that the spirit was with us and that the healing was happening for our people.”

She said the ceremony was important not just in healing, but in educating.

“People need to understand what happened to the Indian people and Black people in this area,” Hansen said. “Yet we’re still here, we’re still fighting and we’re still strong. We’re fighting for future generations that they are not afraid to say who they are and to stand up. I understand development. Development has to happen, but at what price?”

***

The Dewitts have hired a private firm to survey their land and find the Scott Cemetery boundaries this week, according to Bill DeWitt. He said he and his wife support the coalition “100 percent.”

As for the county, public works director Tom Smith told Native News Online they’re working on a program to notify property owners of any potential historic cemeteries that may be on their land, in the hopes of avoiding similar issues in the future.

“This is a problem not only in Prince William,” he said. “It's a problem throughout the country.”

More Stories Like This

Native News Weekly (August 25, 2024): D.C. BriefsUS Presidents in Their Own Words Concerning American Indians

Native News Weekly (December 14, 2025): D.C. Briefs

Wounded Knee Massacre Site Protection Bill Passes Congress

Two Murdered on Colville Indian Reservation

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher