- Details

- By Neely Bardwell

Michigan State University (MSU) hosted three Indian boarding school survivors on April 6 to share their stories to a packed auditorium of those familiar and unfamiliar with the horrors of the boarding school era.

The event — titled “Our Stories Heal – Ginoojimomin Apii Dibaajimoyang” — was hosted by MSU’s Indigenous Law & Policy Center, Native American Institute and American Indian and Indigenous Studies and the Native Justice Coalition.

The topic of Indian boarding schools can be uncomfortable for audiences, and it was apparent as the three Indian boarding school survivors spoke about their painful experiences. However, the survivors acknowledged sharing their stories served as an opportunity for them to heal.

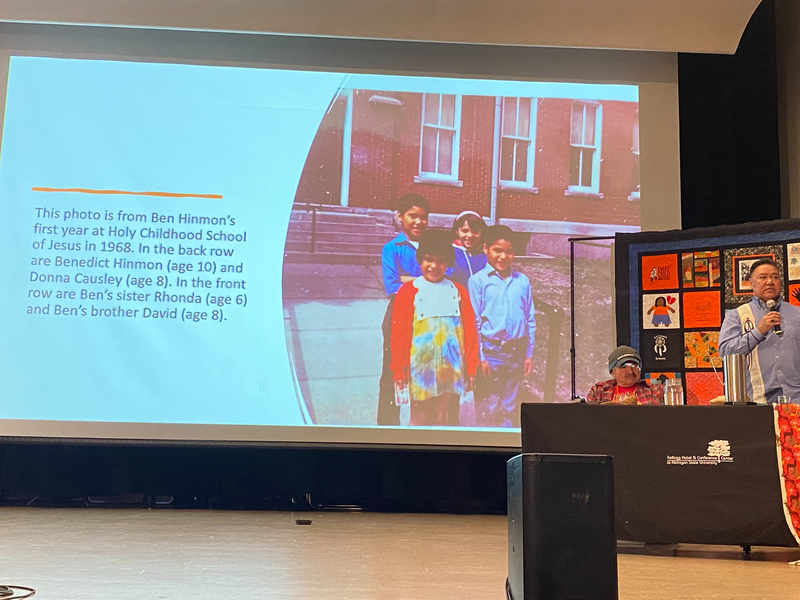

The three survivors — Tom Biron (Garden River First Nation of Ojibway), Linda Cobe (Lac Vieux Desert Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians), and Ben Hinmon (Saginaw Chippewa Tribe of Michigan) — all attended Holy Childhood of Jesus, one of Michigan’s five federally funded boarding schools located in Harbor Spring.

Last August, the Department of the Interior’s The Road to Healing tour made a stop in Pellston, Michigan, just outside of Harbor Springs, to collect the stories from survivors and their descendants of Holy Childhood.

Wenona Singel, director of the MSU Indigenous Law & Policy Center, shared some history about boarding schools with the attendees.

“We have five Indian boarding schools, one of which was federally operated, and the other four of which receive federal funds to operate,” Singel explained to the audience.

“In many cases where these schools operated, they were receiving funds that were supposed to be paid to tribes for this secession of their traditional homeland. Instead, the money was spent on education systems which abused and forcibly assimilated native children.”

Biron, Cobe and Hinmon shared stories of the physical and emotional abuse and neglect they endured at the hands of the school — and the trauma they carry with them today.

“I was a residential student there from the fall of 1968 through the summer of 1971,” Hinmon said. “And at that point, I had escaped from that school. One of the most significant traumas I think I went through as a young man, as the eldest son of this family, was not being able to protect her [younger sibling]. They were little, and I felt powerless to be able to take care of them. I witnessed their suffering, the suffering of other children that attended school, and it was that general sense of powerlessness that we learned over the years that we were there.”

Biron, who was visibly uncomfortable on stage while speaking, shared his unique story with trauma that he is still recovering from today. While referring to a photo of him and his siblings, he talks about his posture.

“That’s [the photo] in the parlor,” Biron told the audience. “It’s around Christmas. I turned six years old. The posture I’d taken in the picture — I still do that sometimes. It’s like I need to go up against the wall and look out visually. I don’t really want to see everything. I don’t want to hear much. I don’t want to be a part of things. I know it’s still in my behavior. The picture is kind of deceiving. We weren’t together.”

When it was revealed that Holy Child did not close until 1983, there was an audible gasp in the auditorium, followed by one audience member saying, “Oh my God.”

Even though it has been decades since the three attended Holy Childhood, it is still difficult to talk about the trauma they experienced, according to Cobe.

“I tell my story because I know there’s many out there who can’t,” Cobe said. “My language was taken from me; my childhood was taken; my culture was taken. But we have the opportunity today to get that all back.”

Biron shared a story where the emotions he pushed down came back up during his keynote speech at a substance abuse recovery event in Toronto.

“I got up on that stage and was supposed to say something about healing and recovery — I just lost it,” he said. “What came out of my mouth was, ‘What they did to my family.’ That’s what came up. That was my keynote speech.”

More Stories Like This

Native Americans Could Be Hit Hard as Education Department Resumes Student Loan Wage GarnishmentHanging a Red Dress for Christmas: MMIP, Native Higher Education, and Hope for a Better New Year

Native Students Can Win $5,000 Scholarship, International Distribution in Pendleton Design Contest

American Indian College Fund Raises Alarm Over Plan to Shift Native Programs Away From the Dept. of Education

MacKenzie Scott Foundation Gives $5 Million Contribution to Little Priest Tribal College

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher