- Details

- By Chez Oxendine

Nickolaus Lewis, a member of the Lummi Nation Tribal Council, has watched his community suffer loss after loss this year to opioid overdoses. Two of the victims have been infants.

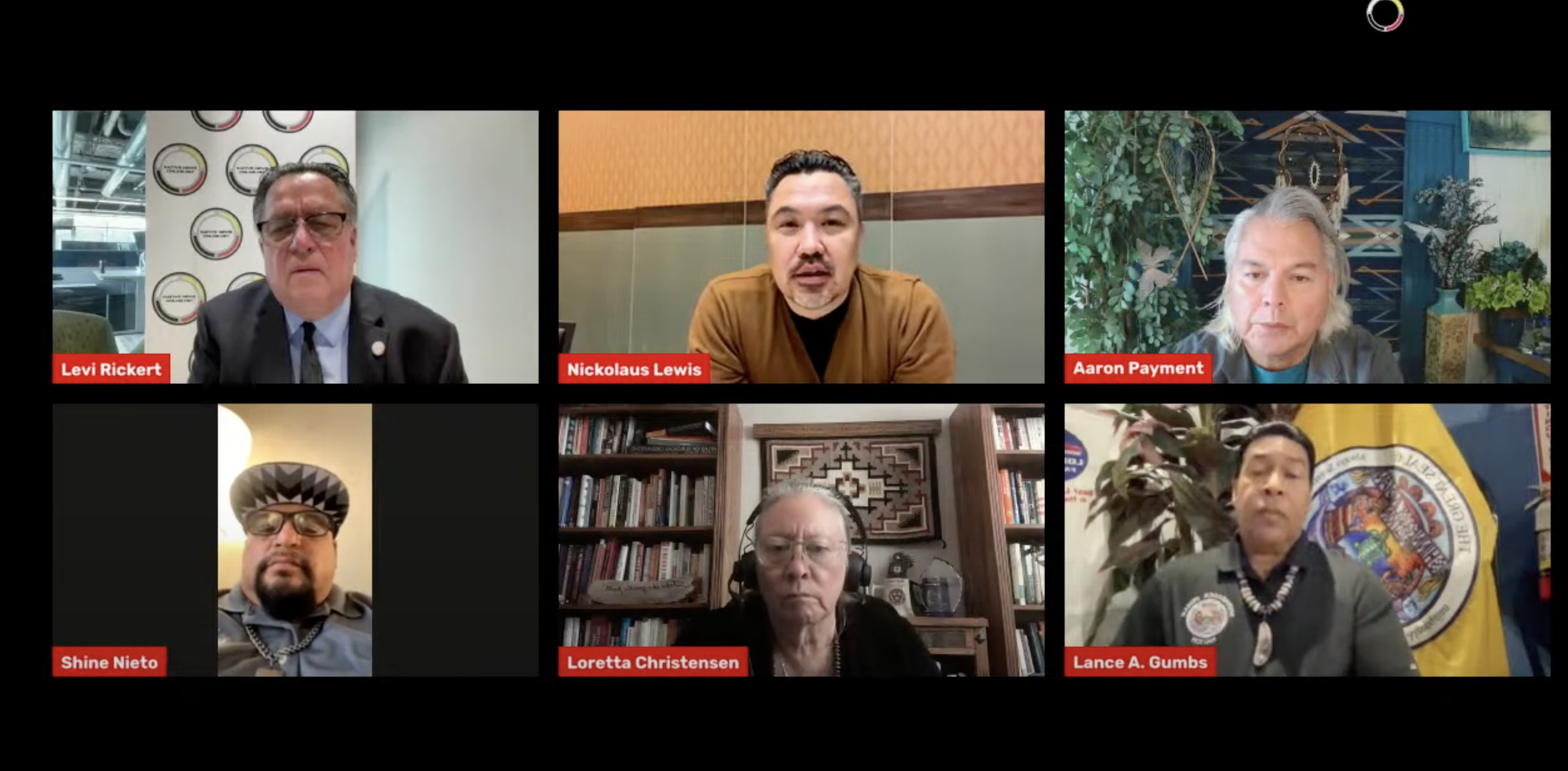

Lewis, who also serves as the vice chair on the National Indian Health Board, as well as the vice chair on the Tribal Self Governance Board, and as the chairman on the Northwest Portland Indian Health Board, spoke to viewers during a Native News Online panel on reducing overdose deaths in Indian Country, held in late October.

The situation in Lummi Nation has left some families losing multiple relatives in short time, said Lewis. The frequency of overdose deaths means some families are attending “twenty to thirty funerals a year.”

“That’s trauma, that’s continuing the cycle of trauma,” Lewis said. “That’s what we’re seeing in our community as well as communities across the country.”

The data bears that out: in 2020, CDC data indicated that Indian Country saw a 39 percent spike in opioid overdoses, killing more than 7,500 people. The opioid epidemic has hit Native Americans especially hard, killing Indigenous people at 2.6 times the rate of white Americans.

The symptoms of the overdose epidemic are varied and nuanced, ranging from death to a sense of disconnection from one’s community and family while grappling with addiction. In response, Indian Country has mounted a growing number of harm reduction efforts, such as distrirbuting Nalaxone, a life-saving overdose reversal medication, into the community, and creating access to medically assisted treatment to ease withdrawal symptoms.

Dr. Loretta Christensen, a Navajo tribal member and Chief Medical Officer at the Indian Health Service, called the epidemic “catastrophic.” Christensen said her department has ramped up pre-hospital care and screenings, and done their best to take “whatever opportunity they can” to save lives at all stages of a hospital visit owing to an opioid overdose.

“We're trying to give every opportunity to save lives — we'd like to eradicate the drugs completely but we know right now saving lives is our primary goal,” Christensen said. “We're here to support and really push that forward for all of our communities so we can save people's lives and give them another day to get their footing.”

That’s the goal at Bishop Paiute’s harm reduction program, where Arelene Brown, a tribal member and recovery support specialist, manages the use of medically assisted treatment to help people enter and sustain recovery from addiction. Medically assisted treatment carries with it a stigma, however, that has prevented the practice from catching on in places where it would help most, Brown said.

That stigma has to stop so that tribes can begin employing more aggressive life-saving measures like the aforementioned medically assisted treatment or widespread use of Naloxone, Brown said.

“So many things are stigmatized,” Brown said. “Narcan is discriminated against. Addiction recovery services are discriminated against. People who are new to recovery suffer stigma. It exists on so many levels, but it also prevents people from getting well. One of the things that sticks with me is that it's blatant discrimination and in this day and age, discrimination kills.”

Dr. Aaron Payment, former tribal chair for the Sault Ste. Marie tribe and vice president of tribal relations and learning at health consultancy Kaufmann and Associates, echoed the sentiment. In his years in the tribal leadership, including a stint as Director of Government Relations at the National Indian Health Board, Payment has seen a “backlash” to drug treatment solutions thanks to “false starts” under other proposed solutions.

That’s why medically assisted treatment in particular has taken so long to catch on, Payment said -— but it’s time to start using it to save people’s lives, he added.

“Treating a drug addiction with other drugs became this idea of, no, they have to be completely clean,” Payment said. “Our people that are dying need our compassion and care, not our judgment, and so we have to do whatever it takes. We could form an opinion about how you can get healthy, and let people die who don't get there, or we could help them and save somebody's life along the way.”

While much of the Native News Online talks discussed ongoing solutions to existing addictions, Shinnecock Nation tribal ambassador Lance A. Gumbs pointed instead to the “root causes” of drug use, including plummeting standards of living and economic stress.

Gumbs shared with panelists the story of his son, who died from a fentanyl overdose after using cannabis laced with the drug. He pointed out that he never drank alcohol, smoked, or used drugs. Gumbs says he gave his son a perfect role model, yet his son tried drugs and paid the ultimate price for it. He also pointed out, his son was well-provided for economically, but it was not enough. Gumbs said he couldn’t initially fathom why his son had turned to using drugs — but after speaking with his son’s friends, he began to understand what youth were facing that pushed them toward “escape.”

Treating addiction after the fact is a necessary step, Gumbs said, but so is building community and safety.

“I think it's a greater problem in the fact that our children, our kids, or these individuals who are doing this have this sense of hopelessness or despair and turn to these narcotics as an escape,” Gumbs said. “It's not something we're going to solve with medication or the ability to get the word out. We have to find the root cause and that has a lot to do with living conditions and the family structure, it has a lot to do with the tribal structure, it has a lot to do with all of these components.”

These above speakers and sentiments were a fraction of the solutions and stories shared during two live streams held on the Native News Online Facebook page in late October. The livestreams were sponsored by Cherokee Nation, Running Strong for American Indian Youth, and Kauffman and Associates Inc. Full panels can be found here (Part 1,) and here (Part 2.) Coverage of the opioid epidemic will continue well beyond these two live streams, Publisher Levi Rickert said.

“Native News Online knows two live streams won't solve the problem of opioid overdoses in our country,” Rickert said. “But we know we must do our part, and use our platform, to contribute to the healing of tribal communities.”

Tell Us What You Think

More Stories Like This

Rez Vet Earns Global Recognition for Serving Navajo Nation's AnimalsChickasaw Nation Governor Bill Anoatubby leads groundbreaking for pediatric clinic

Cherokee Nation Eyes $4 Million Transitional Housing Program

Indian Health Service Reflects on 2025; Touts Facility Expansions, Workforce Development

Senate Committee on Indian Affairs to Host Hearng in Bills to Beneift Tribal Health Programs