- Details

- By Laureli Ivanoff

Everyone had a job. The men and boys drove the boats upriver to dip the nets in the river and seine. The women waited. Never wondering. There were always enough. The salmon that filled the boats when they returned weren’t huge — humpies aren’t — maybe a foot long. But they were plentiful and made for good drying.

Editor's Note: This article was originally published by High Country News. Used with permission. All rights reserved.

My cousins and I played in the water. Swimming. Doing somersaults or handstands, holding our breath, eyes closed tight, our hands squishing in the mud on the slough side of the sandbar island our family called Eaton Station, in the Unalakleet River. Eaton Station: The best resort. We played badminton in the sand. Tanned on hand-sewn calico blankets laid on the beach. We ate Norton Sound red king crab, fatty grilled king salmon, and, if we were lucky, akutaq made by Mom or an auntie. It seemed like the sun was always shining. And it probably was. Climate change wasn’t a part of our daily vocabulary, and persistent summer rains and winds weren’t a thing back then. July was for sun and salmon.

Once the boats returned, slow and heavy, the women gathered at the fish-cutting tables. My favorite part. They said funny things when they were working. They always knew the answer to everything. They always seemed to be smiling and laughing. The cumulus clouds above us, like whipped cream on grandma’s white cake with a sprinkle of fresh tart blueberries, laughed with them. My belly, my cheeks, my jaw, the oil and juice making up my eyeballs relaxed. Safe. So safe.

Life flowed easy.

My first job at the cutting table, when I was maybe 7 or 8, was to clean the slime and blood off the fish my aunties and Mom cut for drying. Three fish in each hand, I’d wade out on the river side of the island, the sun so hot it didn’t matter that the water was cold. I’d go past my knees, far enough to ensure that the fillets, attached by the tail, wouldn’t touch the river bottom and stayed free of any sand. I swished the orange flesh in the sparkling, fresh, clear water. The gulls, those greedy cousins, flying and squawking for any piece of flesh or eggs. Or milt — now and then I’d toss a piece of the white sac from a male, just to see it disappear whole, the gull’s head tilted to the sky.

Once the boats returned, slow and heavy, the women gathered at the fish-cutting tables. My favorite part.

One day, Mom handed me her ulu at the fish-cutting table. It was a graduation. A commencement. I was on to bigger things, the handover said. I was ready to learn the real craft. With real technique. With her favorite tool. I didn’t realize that from that point on, I’d stand at the table with Mom and my aunties and learn the secrets of the world when the boats came back.

With guidance from Mom, I cut my first humpie, a small female. I sliced down the belly, pushing harder than I anticipated. Then down the back. A few other cuts, and the fillets were attached at the tail, ready for the tirraqs, or angled slices, that ensure bite-sized bits in winter. When I was done, the heart was still attached. The purple morsel hung from the collar at the bottom of the fillet. I didn’t know that leaving the heart attached to dry was considered a skill. I hadn’t meant for that to happen.

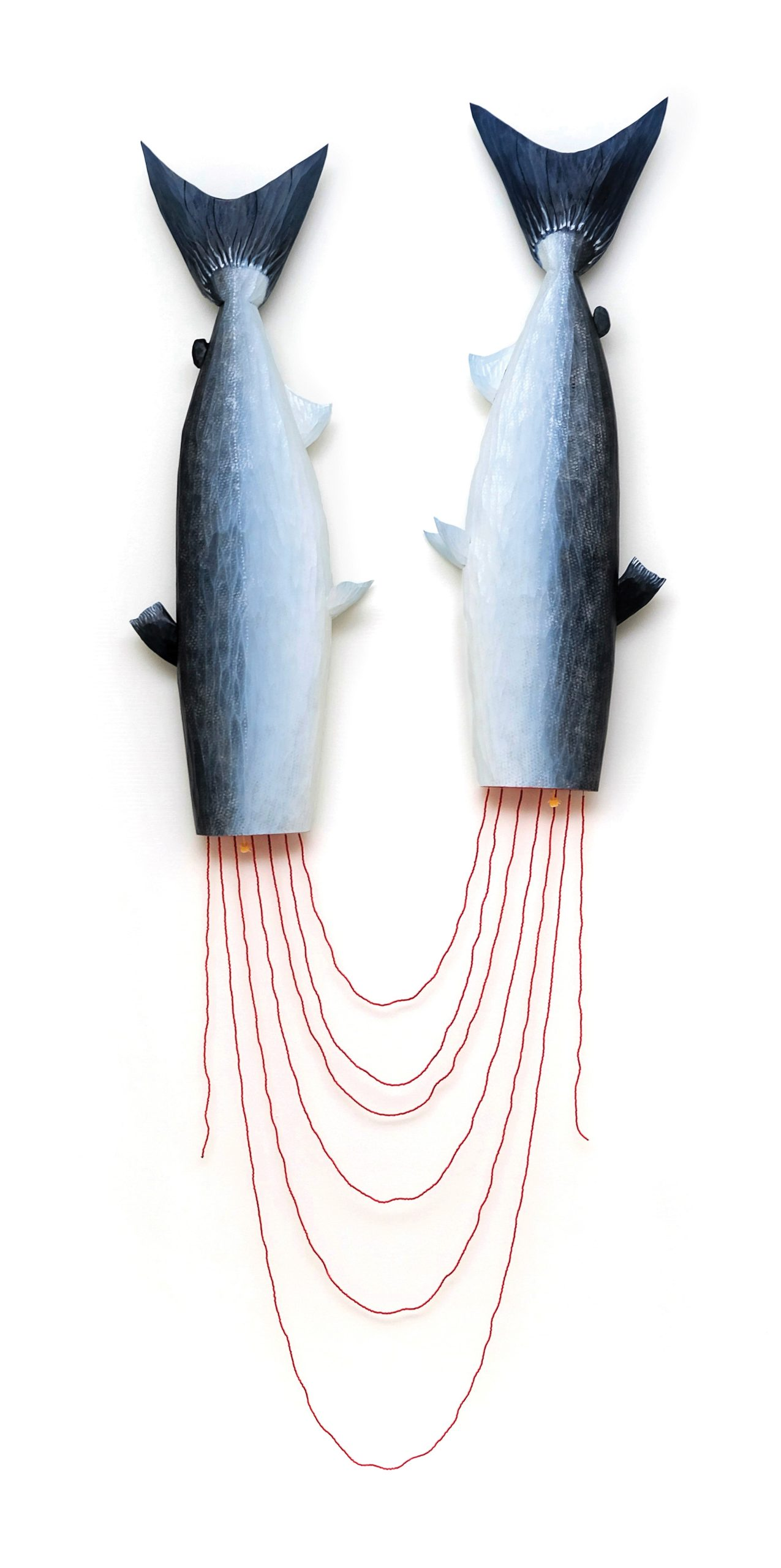

Iqalukpik (salmon) double from Kenai Lake. Erin Ggaadimits Ivalu Gingrich/High Country News“Wow, Paniuq!” Papa Ralph said, his voice ebullient, like cold Tang. “The heart still on there! The best way!”

Iqalukpik (salmon) double from Kenai Lake. Erin Ggaadimits Ivalu Gingrich/High Country News“Wow, Paniuq!” Papa Ralph said, his voice ebullient, like cold Tang. “The heart still on there! The best way!”

Papa handed me my diploma with those words. Words warmed by the love and pride in his inflection, feelings that also flowed from his eyes and heart that day at Eaton Station. Words I can return to any time, to feel grounded in love. I am important, he said to me. I will do important work, he said to me. I am doing good, he said to me.

The pride seeped through my marrow. I waded out into the clean water of the river and swished the humpie, the cottonwoods and birches on the other side of the river practically clapping for me. I hung the cut fish on the drying rack made of cottonwood poles that my dad, brother and uncles put up every year.

I am important, he said to me. I will do important work, he said to me. I am doing good, he said to me

We no doubt ate uuraq that night for supper. Boiled pink salmon steaks and fish eggs with onions, potatoes, salt and pepper in a broth like no other. Mom would have put either kimchi or ketchup in hers. Dad, seal oil. If there was leftover uuraq in Mom’s stainless steel pot, blackened on the bottom from the fire, she tossed it into the river. White fish and grayling ate the pink meat and boiled eggs. We washed out our bowls at the river, using sand as dish soap for scrubbing.

My job of cutting fish returns, year after year. My favorite job. My favorite job because, thanks to my teachers, it is done with love and was born from love. Because we all work together, and together is the cornerstone of everything that gives meaning in life. My favorite job because cutting fish means I belong. To a family, to a community that shares, and in the process of doing, I remember I belong to a long line of ancestors who made cuts just like the ones my mom showed me. It’s more than just food for the winter. Salmon remind me that I am important and loved.

Help us tell the stories that could save Native languages and food traditions

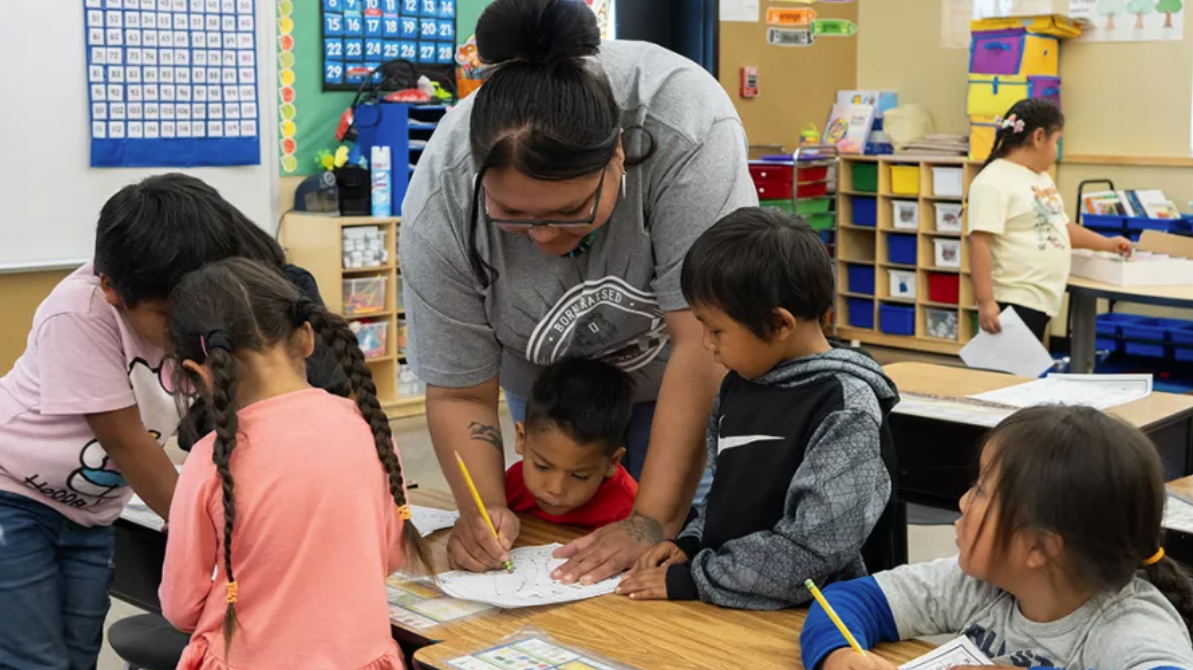

At a critical moment for Indian Country, Native News Online is embarking on our most ambitious reporting project yet: "Cultivating Culture," a three-year investigation into two forces shaping Native community survival—food sovereignty and language revitalization.

The devastating impact of COVID-19 accelerated the loss of Native elders and with them, irreplaceable cultural knowledge. Yet across tribal communities, innovative leaders are fighting back, reclaiming traditional food systems and breathing new life into Native languages. These aren't just cultural preservation efforts—they're powerful pathways to community health, healing, and resilience.

Our dedicated reporting team will spend three years documenting these stories through on-the-ground reporting in 18 tribal communities, producing over 200 in-depth stories, 18 podcast episodes, and multimedia content that amplifies Indigenous voices. We'll show policymakers, funders, and allies how cultural restoration directly impacts physical and mental wellness while celebrating successful models of sovereignty and self-determination.

This isn't corporate media parachuting into Indian Country for a quick story. This is sustained, relationship-based journalism by Native reporters who understand these communities. It's "Warrior Journalism"—fearless reporting that serves the 5.5 million readers who depend on us for news that mainstream media often ignores.

We need your help right now. While we've secured partial funding, we're still $450,000 short of our three-year budget. Our immediate goal is $25,000 this month to keep this critical work moving forward—funding reporter salaries, travel to remote communities, photography, and the deep reporting these stories deserve.

Every dollar directly supports Indigenous journalists telling Indigenous stories. Whether it's $5 or $50, your contribution ensures these vital narratives of resilience, innovation, and hope don't disappear into silence.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Native languages are being lost at an alarming rate. Food insecurity plagues many tribal communities. But solutions are emerging, and these stories need to be told.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Native languages are being lost at an alarming rate. Food insecurity plagues many tribal communities. But solutions are emerging, and these stories need to be told.

Support independent Native journalism. Fund the stories that matter.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher