- Details

- By Professor Victoria Sutton

Ireland once had its own indigenous legal system, called Brehon law, originally written between the 7th and 8th centuries. These laws including governance of the ancient feast of Samhain or the old spelling, Samain (pronounced SOW-han).

Beginning as All Saints Day on May 13th, the Catholic Church sought to make this day important and overshadow the pagan holidays. Pope Gregory III in the 8th Century moved All Saints Day to November 1st to divert attention to All Saints Day (we are told by historians) in order to diminish the wildly popular October 31st, Samhain. In the process, Samhain became the evening before All Hallows Day, or Hallows Eve, and today, Halloween.

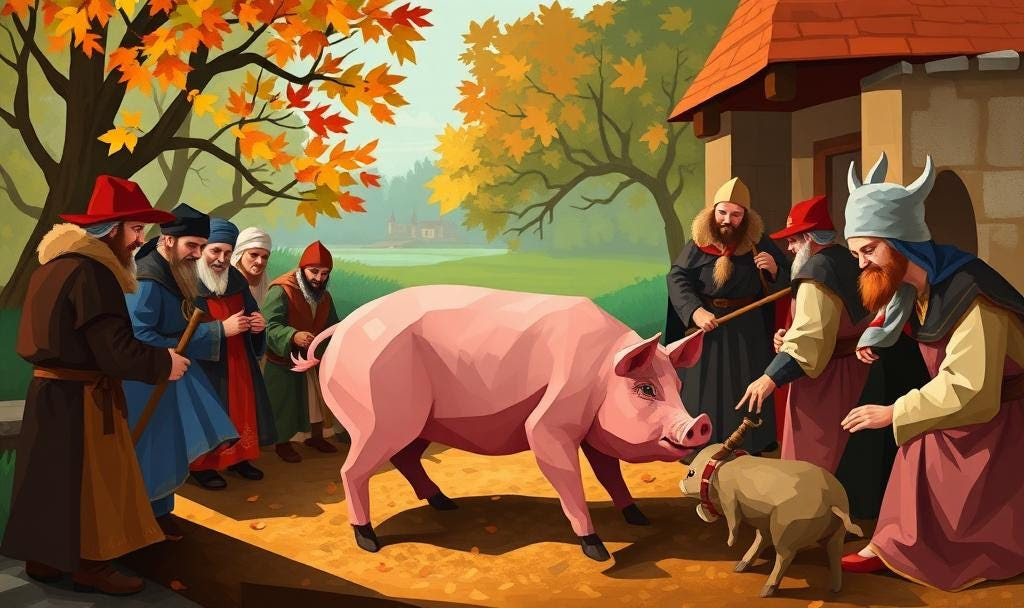

In this particular law focused on the sacrificial animal of Samhain — pigs.

Samain also marked the end of the pig-hunting season and the start of a new breeding cycle running from November to January. Pigs, particularly wild boar, are strongly associated with Samain in a number of sources. The Irish boar carried supernatural connotations, listed as one of the animals that could shapeshift into human form and travel to the otherworld. Regional kings are also recorded as having exacted substantial tributes of boar from their vassals at Samain. The pig was thus the sacrificial animal of Samain.

The legal implications of Samain feasting were significant and it was clearly a time of tension. The law tract Dliged Raith 7 Somaíne la Flaith, translated to ‘right of a fief and renders of a lord’, directed that a lord was entitled to demand a feast from a fief with a retinue of eight men for the Samain feast. If the feast was not up to their standards, heavy fines could be levied. The law (right of a fief and renders of a Lord) indicates: ‘If the Samain feast has failed, two séts for its failure, with doubling of restitution of whatever has failed’ (translation). According to scholar John Biggins, a sét here was probably equivalent to one milch cow and one heifer, so no small penalty. A later reading seems to assume the thing most likely to ‘fail’ was the pig meat offering, referred to as ‘the tested young pig of the feast of St. Martin or of Samain‘ (translation).

Native America and Colonists

Our timeline in America begins with the arrival of Columbus with three pigs in 1493 on his second voyage to Hispaniola in the Caribbean. But it is not until 100 years later with Hernando De Soto’s quest for gold and his expedition through North Carolina that pigs were introduced to Native America on the mainland. DeSoto took 13 pigs that remained of the Columbus original three in the Caribbean and brought them to North Carolina. Those 13 pigs became 700 pigs within three years and pig production was adopted by North Carolina Tribal Nations. They were easy to raise on small plots of land, easy to hide from colonists and marauding enemies. There are colonial records of Indians’ pigs foraging in the neighbor’s gardens and crops and causing property damage, as this practice grew. Pig stealing was a common crime, and Native Americans and people of color were singled out for more extreme punishment for these “pig laws” during the 19th century.

As Native American Tribes were forced onto reserved lands beginning in the East and later in the West, breeding pigs were taken along to ensure the community had food.

The Role of the Sacrificial Pig in Fall, Colonial and Later America

The U.S. has a history of significant Irish and Scottish settlers in America, so it is no surprise they brought the big killing tradition with them. In the Appalachians, famously settled by Scots, Irish and Scots-Irish, there was a community “hog killin’” in the fall after the first frost. That was the best time to kill a hog (I am told). So is it possible it was a tradition brought from its beginnings in the 7th and 8th century Samhain in Celtic Ireland?

Modern Hog Killing

Family farms with hogs for their own use, and not a USDA regulated facility, are exempt from federal law as it applies to hog processing. However, state cruelty laws apply, and require you to humanely kill the hog. A little less than a century ago, it was a community event and every family took home salted pork for the winter. But could you do that today?

This video is a similar process including some Appalachian traditions, but vastly different from the tradition a century ago when there was no electricity, no heavy diesel equipment and no power tools:

[(Video not included in this version)]

Exemption from federal meat inspection rules does not mean you are exempt from all rules. Local governments also have health and safety codes and prohibit the sale of meat. Thus, it must be gifted.

New Traditions — Regulated

Culture is not alive if it is not changing, so I have heard pigs make pretty good pets. BUT, they are also regulated by local governments, and you may need a permit to keep a pot-bellied pig, for example. Some local governments classify pigs as livestock and so the zoning of your property would be a determining factor. Local health and safety codes regulate smell and waste disposal. Some local governments classify pigs as “exotic pets” requiring special permits or prohibited all together.

Final Thought. . .

We did not have time to get to some of the bad outcomes from pig farming (feral pigs overrun parts of America today and they can kill you and eat you without a trace); or the amazing things (like pig heart valves that are now used to save human lives).

That said, the sacrifice of the pig is not the first thing we think of when we think of Halloween. But Samhain or Halloween may mark an early beginning of our long great love affair with the pig, its close association with human life and one worth remembering on Halloween.

As always, this is not legal advice and you need to check with a lawyer if you want to do almost anything . . .

If you would like a unique gift for Halloween, I recommend Halloween Law: A Spirited Guide to the First Year Law Curriculum for $12.99.

To read more articles by Professor Sutton go to: https://profvictoria.substack.

Professor Victoria Sutton (Lumbee) is Director of the Center for Biodefense, Law & Public Policy and an Associated Faculty Member of The Military Law Center of Texas Tech University School of Law.

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher